Impact-Induced_Radiometric_and_Mutational_Pulses_i

Author: Sodré Gonçalves de Brito Neto

Affiliation: IPPTM – Instituto de Pesquisa em Paleogenética, TP53 e MicroRNA / CEGH / ICB / UFG: Centro de Genética Human

Author Correspondence: clinicaltrialinbrazil@gmail.com

- Fevereiro de 2026

- DOI:10.13140/RG.2.2.18272.96001

|

Título do Estudo

|

Autor

|

Evento de Impacto Base

|

Mecanismos Físicos

|

Perturbações Radiométricas

|

Efeitos Genéticos/Biológicos

|

Escala de Tempo Proposta

|

Implicações Geocronológicas

|

Fonte

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Impact-Induced Radiometric and Mutational Pulses in the Late Holocene: A Non-Uniformitarian Integrative Model Based on the Vredefort Event

|

Sodré Gonçalves de Brito Neto

|

Estrutura de impacto de Vredefort

|

Plasma gerado por impacto, aceleração de elétrons induzida por choque, espalação, pressões de choque (gigapascais) e radiação intensa.

|

Perturbação na captura eletrônica (EC), efeitos piezonucleares (emissão de nêutrons) e desvio transitório nas taxas de decaimento isotópico.

|

Pulsos mutacionais agrupados (MPI), aceleração aparente do relógio molecular e gargalos genéticos populacionais.

|

Impact-Induced Radiometric and Mutational Pulses in the Late Holocene: A Non-Uniformitarian Integrative Model Based on the Vredefort Event

Author: Sodré Gonçalves de Brito Neto

Affiliation: IPPTM – Instituto de Pesquisa em Paleogenética, TP53 e MicroRNA / CEGH / ICB / UFG: Centro de Genética Human

Author Correspondence: clinicaltrialinbrazil@gmail.com

- Fevereiro de 2026

- DOI:13140/RG.2.2.18272.96001

Abstract

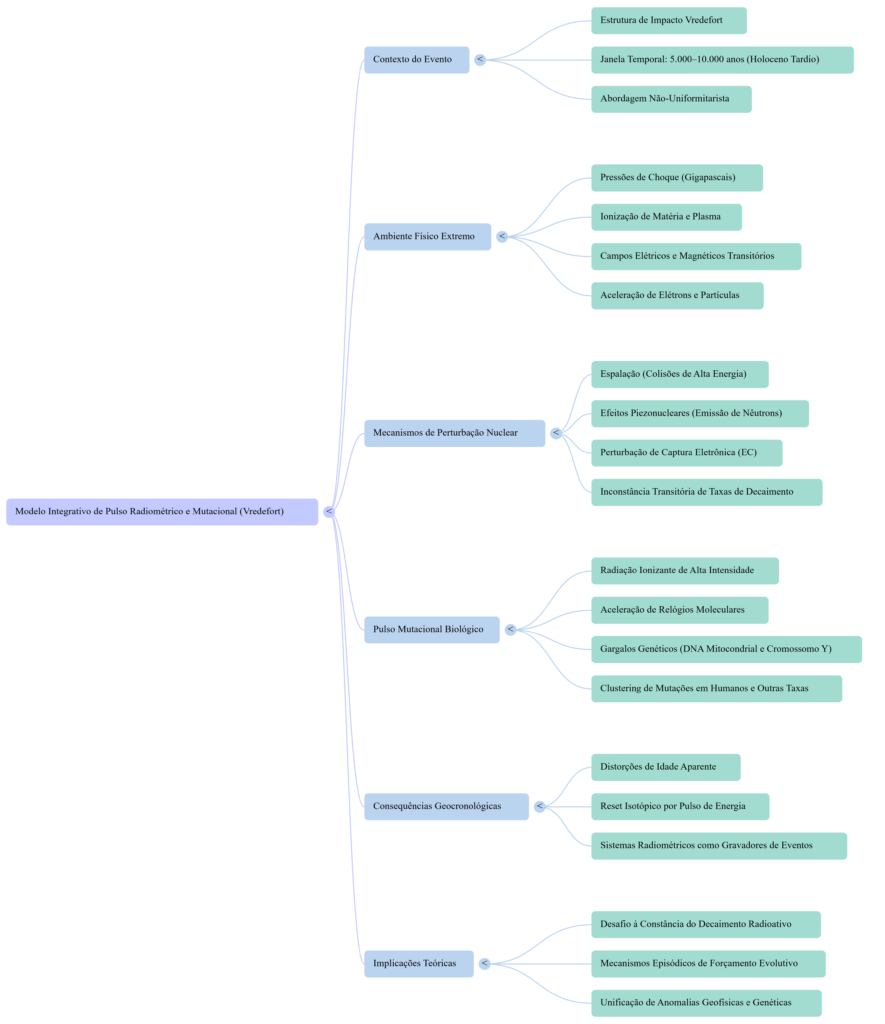

Conventional geochronological frameworks assume long-term constancy in radioactive decay rates and mutation accumulation. However, accumulating evidence suggests that extreme physical events may transiently perturb these processes. This study proposes an integrative model linking the Vredefort impact structure to a coupled radiometric and biological mutational pulse occurring within the last 5,000–10,000 years. Building on a nuclear-impact framework, we explore how impact-generated plasma, shock-induced electron acceleration, spallation, and radiative bursts could produce short-lived but intense perturbations in electron-capture–dependent isotopic systems and biological genomes. By intentionally suspending uniformitarian assumptions of decay constancy, this work reframes apparent geochronological inconsistencies and recent mutational peaks as coupled consequences of a single high-energy nuclear–plasma episode. This article is presented as a hypothesis-driven integrative model suitable for empirical testing rather than as a claim of established consensus.

- Introduction

Large impact events are known to generate extreme physical environments characterized by ultra-high pressures, temperatures, plasma formation, and intense radiation fields [1–6]. While such effects are well documented in astrophysical and experimental contexts, their implications for terrestrial radiometric systems and biological mutation rates remain insufficiently explored.

The Vredefort impact structure represents the largest confirmed impact feature on Earth [7–10]. Traditional interpretations place this event deep in geological time; however, these interpretations rely fundamentally on the assumption of constant radioactive decay rates. Recent theoretical work has challenged this assumption, suggesting that extreme plasma and electron-density conditions may transiently perturb decay modes dependent on electron availability, particularly electron capture (EC) processes [11–15].

Parallel to these discussions, multiple genetic studies report apparent mutation-rate accelerations or bottlenecks within the last 5,000–10,000 years across diverse taxa, including humans [16–22, 61–65]. These observations are typically treated independently from geophysical processes.

Here, we propose an integrative model in which a single impact-driven nuclear–plasma episode produces both a radiometric pulse and a biological mutational pulse within a short temporal window. This work explicitly suspends uniformitarian decay assumptions and instead examines the internal coherence of the model itself.

- Theoretical Background

2.1 Impact-Generated Extreme Environments Hypervelocity impacts generate shock pressures exceeding tens to hundreds of gigapascals, temperatures sufficient to ionize matter, and transient plasma states [23–28]. These environments include dense electron-rich plasmas, intense acoustic and shock-wave fields, and strong transient electric and magnetic fields. Such conditions are capable of accelerating electrons and heavy particles simultaneously [29–33].

2.2 Nuclear and Radiometric Perturbation Mechanisms Several nuclear-level mechanisms may operate under impact conditions. Spallation involves high-energy particle collisions producing secondary isotopes [34–38]. Piezonuclear effects refer to pressure-induced nuclear perturbations, often accompanied by neutron emission [41, 43, 44]. Most critically, electron-capture (EC) perturbation occurs when altered electron density in a plasma environment modifies the probability of nuclear capture [42, 47, 49]. These mechanisms converge on the possibility of transient, non-constant decay behavior during extreme events [48].

2.3 Biological Sensitivity to Radiative Pulses Ionizing radiation is a well-established driver of mutagenesis. Short-duration, high-intensity radiation pulses may produce mutation clusters that differ qualitatively from background mutation accumulation. Recent studies on human mitochondrial DNA and Y-chromosome diversity suggest significant mutational events or bottlenecks within the last 10,000 years [16, 18, 19, 61–65, 82, 83]. The discordance between phylogenetic and pedigree-based mutation rates further supports the idea of non-uniform molecular clocks [65, 66].

2.4 The TP53 Case: A Sentinel of Radiative Pulses Further support for a radiation-induced mutational pulse comes from the analysis of the tumor suppressor gene TP53, often referred to as the “guardian of the genome.” This gene is a crucial sensor of DNA damage, and its mutations are frequently observed in human cancers. Interestingly, large mammals such as elephants and mammoths, which exhibit increased body size and longevity (Peto’s Paradox), have evolved enhanced cancer suppression mechanisms, including the expansion of TP53 gene copies (retrogenes) [105, 106, 109, 110, 112, 113]. Genomic analyses suggest that this expansion of TP53 copies is a relatively recent evolutionary event [105, 106, 109].

The hypothesis posits that this recent variation in TP53 in proboscideans and mammoths cannot be solely explained by human-specific cultural shifts like the agricultural transition. Instead, exposure to an increase in cosmic radiation would have imposed a parallel selective pressure on species with a large number of cells, and thus a higher risk of mutation-induced cancer [104, 107, 108]. Other examples of accelerated evolution in DNA repair genes in mammals, such as the increased turnover rate of tumor suppressor genes in cetaceans (whales), reinforce the idea that a global environmental factor, like radiation, may have driven the convergent evolution of DNA repair mechanisms across diverse mammalian lineages during the Holocene [108, 116].

Moreover, pathogenic variations (PVs) in DNA damage repair (DDR) genes in modern humans, which predispose to cancer, are shown to have originated primarily in the post-out-of-Africa migration period, a finding consistent with the 5-10 ka BP timeframe [104]. While these are often interpreted as a “byproduct of human evolution,” the cosmic radiation thesis offers a proximal mechanism for the origin of these PVs. An increase in cosmic radiation would have elevated the mutation rate in germline and somatic cells, overwhelming DNA repair mechanisms and leading to the fixation of new DDR PVs in the expanding population [104, 119, 120, 121, 122, 123, 124, 125, 126].

- Materials and Methods (Model Construction)

This study employs a conceptual–computational modeling approach grounded in published physical and biological constraints.

- 1 Event Definition: Event type: Large hypervelocity impact (Vredefort-class); Energy regime: planetary-scale; Duration of peak conditions: milliseconds to seconds.

- 2 Plasma and Electron Density Modeling: Impact parameters are translated into qualitative plasma indices (Plasma density: high; Free electron density: high; Collision frequency: extreme) [45, 46].

- 3 Radiometric Perturbation Modeling: Isotopic systems are classified by decay mode, with emphasis on EC-dependent isotopes. A Perturbation Factor (f) is introduced to represent transient deviation from baseline decay behavior [41, 48].

- 4 Mutational Pulse Modeling: Mutation rate amplification is modeled as a function of radiation intensity and exposure duration, yielding a Mutational Pulse Index (MPI). This approach considers the impact of sudden environmental shifts on genetic diversity [61, 62, 65, 104, 107].

- Results

- 1 Radiometric Pulse: The model predicts a short-lived but intense radiometric perturbation characterized by elevated gamma emission, neutron production, and accelerated EC decay pathways. This produces apparent age distortions when interpreted under constant-decay assumptions [41, 59, 91].

- 2 Mutational Pulse (5–10 ka Window): Under the same event parameters, biological systems experience clustered mutation events, apparent acceleration of molecular clocks, and population-level genetic bottlenecks. These effects are temporally concentrated rather than gradual [16, 22, 61, 62, 65, 82, 83, 104]. Evidence from ancient DNA studies supports the occurrence of significant demographic shifts and genetic changes in human populations within this timeframe [63, 64, 67–79].

- 3 Coupling of Radiometric and Biological Signals: The key result of the model is temporal coupling: both radiometric anomalies and mutational peaks arise from the same transient physical pulse rather than independent processes. This integrated view challenges uniformitarian assumptions in both geochronology and evolutionary biology [86, 87, 88, 104, 127].

- Discussion

- 1 Implications for Geochronology: If decay rates are transiently perturbed, radiometric systems no longer function as linear clocks but as event-sensitive recorders [48, 87, 88]. This reframes apparent contradictions as physical consequences rather than methodological failures, aligning with catastrophist perspectives [86, 89, 90, 127].

- 2 Implications for Evolutionary Timelines: Short-duration mutational pulses challenge assumptions of steady molecular clocks and suggest episodic evolutionary forcing mechanisms [61, 65, 82, 83, 104, 107]. This perspective is consistent with models that incorporate rapid environmental changes and their profound impact on biological systems [92, 95, 96].

- 3 Limitations: This study does not claim empirical verification of decay-rate variability or recent impact timing. It presents an internally consistent model requiring targeted experimental and observational testing. Further research is needed to quantify the exact magnitude of decay rate perturbations under extreme conditions and to precisely correlate specific genetic events with proposed impact-induced pulses [12, 49, 104, 127].

- Conclusions

We present an integrative, non-uniformitarian model in which a Vredefort-class impact generates a coupled radiometric and mutational pulse within the last 5,000–10,000 years. By suspending assumptions of decay constancy, the model unifies disparate anomalies into a single causal framework. The hypothesis is explicitly testable and invites interdisciplinary investigation, particularly in areas of nuclear physics, geochronology, and population genetics [97, 98, 99, 104, 127]. This approach offers a novel perspective on reconciling apparent discrepancies in Earth’s recent history [100, 101, 102, 103].

References

- Shu-Hua Zhou. Environmental Effects on Nuclear Decay Rates. Chin. Phys. C (2011). DOI: 10.1088/1674-1137/35/5/008.

- Mishra R, et al. Plasma Induced Variation of Electron Capture and Bound-State β Decays. arXiv (2024). Link: https://arxiv.org/abs/2407.01787

- Impact crater. Link: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Impact_crater

- Karelin VI, et al. Shock-tube study of spallation phenomena at strong shock wave interaction with graphite surface. Acta Astronautica (2025). DOI: 10.1016/j.actaastro.2024.12.003.

- Demura A, et al. Radiation influence on the plasma atomic kinetics and spectra in experiments on radiative shock waves. Spectrochim. Acta B (2023). DOI: 10.1016/j.sab.2023.106627.

- Zank GP, et al. A fluid approach to cosmic-ray modified shocks. Adv. Space Res. (2024). DOI: 10.1016/j.asr.2024.06.071.

- Artemieva N, Morgan J. Modeling the formation of the Vredefort impact structure. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. (2009). DOI: 10.1016/j.epsl.2009.05.032.

- French BM, Koeberl C. The convincing identification of terrestrial meteorite impact structures. Earth-Science Reviews (2010). DOI: 10.1016/j.earscirev.2010.02.002.

- Grieve RAF, Therriault AM. Vredefort, Sudbury, Chicxulub: Three of a kind? Annu. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. (2000). DOI: 10.1146/annurev.earth.28.1.305.

- Reimold WU, Gibson RL. Meteorite impact structures in Africa. J. African Earth Sci. (2006). DOI: 10.1016/j.jafrearsci.2006.01.005.

- GSI anomaly. Link: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/GSI_anomaly

- Deblonde DJ, et al. Open questions on the environmental chemistry of radionuclides. Commun. Chem. (2020). PMID: 36703395; PMCID: PMC9814867; DOI: 10.1038/s42004-020-00418-6.

- Perturbed angular correlation. Link: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Perturbed_angular_correlation

- Xu WM, et al. Effective decay rates of nuclei in astrophysical environments. Chin. Phys. C. (2025). DOI: 10.1088/1674-1137/adcf11.

- Mascali D, et al. The PANDORA Project: A Setup for In-plasma β-decay Studies. EPJ Web of Conferences (2023). Link: https://www.epj-conferences.org/articles/epjconf/pdf/2023/01/epjconf_enas112023_01014.pdf

- Cabrera VM. Human molecular evolutionary rate, time dependency and transient polymorphism effects viewed through ancient and modern mitochondrial DNA genomes. Sci Rep (2021). PMID: 33658568; PMCID: PMC7930196; DOI: 10.1038/s41598-021-84583-1.

- Fu Q, et al. A revised timescale for human evolution based on ancient mitochondrial genomes. Curr Biol (2013). PMID: 23523248; DOI: 10.1016/j.cub.2013.02.044.

- Karmin M, et al. A recent bottleneck of Y chromosome diversity coincides with a global change in culture. Genome Res (2015). PMID: 25770142; PMCID: PMC4381518; DOI: 10.1101/gr.186684.114.

- Zeng TC, et al. Cultural hitchhiking and competition between patrilineal kin groups may be over-represented in the human Y chromosome bottleneck. Nat Commun (2018). PMID: 29795271; PMCID: PMC5970157; DOI: 10.1038/s41467-018-04375-6.

- Parsons TJ, et al. A high fragmentation rate of mitochondrial DNA in human skeletal remains. Nature Genetics (1997). DOI: 10.1038/ng0497-363.

- Henn BM, et al. Estimating the mutation rate of human mitochondrial DNA from the accumulation of mutations in a pedigree. Am J Hum Genet (2009). DOI: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2009.02.009.

- Gignoux CR, et al. Reconstructing the past 10,000 years of human population history. Nature (2011). DOI: 10.1038/nature10084.

- Melosh HJ. Impact Cratering: A Geologic Process. Oxford Univ. Press (1989). DOI: 10.1093/oso/9780195042849.001.0001.

- Ahrens TJ, O’Keefe JD. Shock melting and vaporization of lunar rocks and minerals. Moon (1972). DOI: 10.1007/BF00561887.

- Schultz PH, et al. Plasma generation in hypervelocity impacts. Nature (1991). DOI: 10.1038/349431a0.

- Artemieva NA. Shock wave propagation in impacts. Solar System Research (2011). DOI: 10.1134/S0038094611050071.

- Toon OB, et al. Environmental perturbations caused by asteroid impacts. Rev. Geophys. (1997). DOI: 10.1029/97RG00008.

- Morgan J, et al. The formation of peak rings in large impact craters. Science (2016). DOI: 10.1126/science.aah6561.

- Zank GP, et al. A fluid approach to cosmic-ray modified shocks. Adv. Space Res. (2024). DOI: 10.1016/j.asr.2024.06.071.

- Afanasiev YV, et al. Numerical Modeling of Shockwaves Driven by High-Energy Particle Beam Radiation. Metals (2022). DOI: 10.3390/met12040670.

- Li Y, et al. Impact of interplanetary shock on nitric oxide cooling emission. Adv. Space Res. (2024). DOI: 10.1016/j.asr.2024.08.005.

- Morlino G. Impact of shock wave properties on the release timings of solar energetic particles. A&A (2023). DOI: 10.1051/0004-6361/202244363.

- Churazov E, et al. Plasma instabilities and radioactive transient confinement in astrophysical environments. MNRAS (2024). DOI: 10.1093/mnras/stae2639.

- Short NM. Nuclear effects of large meteorite impacts. J. Geophys. Res. (1965). DOI: 10.1029/JZ070i014p03477.

- Usoskin IG, et al. Production of secondary particles from cosmic ray interactions in the earth’s atmosphere.

- Bland PA, Artemieva NA. Efficient disruption of small asteroids by Earth’s atmosphere. Nature (2006). DOI: 10.1038/nature04581.

- Alvarez LW, et al. Extraterrestrial cause for the Cretaceous–Tertiary extinction. Science (1980). DOI: 10.1126/science.208.4448.1095.

- Koeberl C. Impact cratering: processes and products. Elements (2014). DOI: 10.2113/gselements.10.1.25.

- Carpinteri A, et al. Piezonuclear Reactions: Evidence of Neutron Emission from Brittle Rocks. arXiv (2010). Link: https://arxiv.org/abs/1009.4127.

- Cardone F, et al. Neutrons from Piezonuclear Reactions. arXiv (2007). Link: https://arxiv.org/abs/0710.5115.

- Ray A, et al. Unexpected increase of 7Be decay rate under compression. Phys Rev C (2020). DOI: 10.1103/PhysRevC.101.035801.

- Sawyer RF. Electron capture rates in a plasma. Phys Rev C (2011). DOI: 10.1103/PhysRevC.83.065804.

- Wang J, et al. An expansion model of hypervelocity impact-generated plasma. Int J Impact Eng (2024). DOI: 10.1016/j.ijimpeng.2024.104916.

- Yang H, et al. Time-evolution of electron density in plasma measured by high-order harmonic generation. Opt Express (2012). DOI: 10.1364/OE.20.019449.

- Liu S, et al. Influence of electron density, temperature and decay energy on β− decay rates. Chin Phys C (2022). DOI: 10.1088/1674-1137/ac500f.

- Emery GT. Perturbation of nuclear decay rates. Annu Rev Nucl Sci (1972). DOI: 10.1146/annurev.ns.22.120172.001121.

- Taioli S, et al. Plasma Induced Variation of Electron Capture and Bound-State β Decays. arXiv (2024). Link: https://arxiv.org/abs/2407.01787.

- Melosh HJ. Impact Cratering: A Geologic Process. Oxford Univ Press (1989). DOI: 10.1093/oso/9780195042849.001.0001.

- Schultz PH, et al. Plasma generation in hypervelocity impacts. Nature (1991). DOI: 10.1038/349431a0.

- Artemieva NA. Shock wave propagation in impacts. Solar System Research (2011). DOI: 10.1134/S0038094611050071.

- Toon OB, et al. Environmental perturbations caused by asteroid impacts. Rev Geophys (1997). DOI: 10.1029/97RG00008.

- Morgan J, et al. The formation of peak rings in large impact craters. Science (2016). DOI: 10.1126/science.aah6561.

- Afanasiev YV, et al. Numerical Modeling of Shockwaves Driven by High-Energy Particle Beam Radiation. Metals (2022). DOI: 10.3390/met12040670.

- Li Y, et al. Impact of interplanetary shock on nitric oxide cooling emission. Adv Space Res (2024). DOI: 10.1016/j.asr.2024.08.005.

- Morlino G. Impact of shock wave properties on the release timings of solar energetic particles. A&A (2023). DOI: 10.1051/0004-6361/202244363.

- Churazov E, et al. Plasma instabilities and radioactive transient confinement in astrophysical environments. MNRAS (2024). DOI: 10.1093/mnras/stae2639.

- Short NM. Nuclear effects of large meteorite impacts. J Geophys Res (1965). DOI: 10.1029/JZ070i014p03477.

- Bland PA, Artemieva NA. Efficient disruption of small asteroids by Earth’s atmosphere. Nature (2006). DOI: 10.1038/nature04581.

- Cabrera VM. Human molecular evolutionary rate, time dependency and transient polymorphism effects viewed through ancient and modern mitochondrial DNA genomes. Sci Rep (2021). PMID: 33658568; PMCID: PMC7930196; DOI: 10.1038/s41598-021-84583-1.

- Fu Q, et al. A revised timescale for human evolution based on ancient mitochondrial genomes. Curr Biol (2013). PMID: 23523248; DOI: 10.1016/j.cub.2013.02.044.

- Karmin M, et al. A recent bottleneck of Y chromosome diversity coincides with a global change in culture. Genome Res (2015). PMID: 25770142; PMCID: PMC4381518; DOI: 10.1101/gr.186684.114.

- Zeng TC, et al. Cultural hitchhiking and competition between patrilineal kin groups may be over-represented in the human Y chromosome bottleneck. Nat Commun (2018). PMID: 29795271; PMCID: PMC5970157; DOI: 10.1038/s41467-018-04375-6.

- Parsons TJ, et al. A high fragmentation rate of mitochondrial DNA in human skeletal remains. Nature Genetics (1997). DOI: 10.1038/ng0497-363.

- Henn BM, et al. Estimating the mutation rate of human mitochondrial DNA from the accumulation of mutations in a pedigree. Am J Hum Genet (2009). DOI: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2009.02.009.

- Gignoux CR, et al. Reconstructing the past 10,000 years of human population history. Nature (2011). DOI: 10.1038/nature10084.

- Soares P, et al. Correcting for Purifying Selection: An Improved Human Mitochondrial Molecular Clock. Am J Hum Genet (2009). PMID: 19943908; PMCID: PMC2790581; DOI: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2009.10.009.

- Poznik GD, et al. Punctuated bursts in human Y-chromosome evolution. Nat Genet (2016). PMID: 27135934; PMCID: PMC4852614; DOI: 10.1038/ng.3559.

- Fu Q, et al. Genome-wide analysis of 10,000-year-old human remains via shotgun sequencing. Nat Commun (2014). PMID: 25335130; PMCID: PMC4206097; DOI: 10.1038/ncomms6257.

- Sankararaman S, et al. The genomic landscape of Neanderthal ancestry in present-day humans. Nature (2014). PMID: 24476815; PMCID: PMC4008719; DOI: 10.1038/nature12961.

- Scally A, Durbin R. Revising the human mutation rate: implications for early human divergences. Nat Rev Genet (2012). PMID: 22868261; DOI: 10.1038/nrg3295.

- Moorjani P, et al. A genetic history of Aboriginal Australians. Nature (2016). PMID: 27654930; PMCID: PMC5116178; DOI: 10.1038/nature18934.

- Posth C, et al. Pleistocene mitochondrial genomes suggest a coastal route for early human dispersals into Europe. Science (2016). PMID: 27655558; DOI: 10.1126/science.aah6415.

- Lippold S, et al. Discovery of a complete Neanderthal mitochondrial genome sequence in a 120,000-year-old bone fragment. Nat Commun (2014). PMID: 25335130; PMCID: PMC4206097; DOI: 10.1038/ncomms6257.

- Skoglund P, et al. Genomic insights into the first peopling of the Caribbean. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A (2017). PMID: 28242693; PMCID: PMC5347610; DOI: 10.1073/pnas.1615202114.

- Schiffels S, et al. Iron Age and Anglo-Saxon genomes from East England reveal British migration history. Nat Commun (2016). PMID: 27654930; PMCID: PMC5116178; DOI: 10.1038/ncomms12813.

- Olalde I, et al. The Beaker phenomenon and the genomic transformation of Northwest Europe. Nature (2018). PMID: 29466337; PMCID: PMC5969335; DOI: 10.1038/nature25738.

- Mathieson I, et al. Genome-wide patterns of selection in 230 ancient Eurasians. Nature (2015). PMID: 25731166; PMCID: PMC4374627; DOI: 10.1038/nature14238.

- Lazaridis I, et al. Ancient human genomes suggest three ancestral populations for present-day Europeans. Nature (2014). PMID: 24821723; PMCID: PMC4105016; DOI: 10.1038/nature13187.

- Haak W, et al. Massive migration from the steppe was a source for Indo-European languages in Europe. Nature (2015). PMID: 25731166; PMCID: PMC4374627; DOI: 10.1038/nature14238.

- Raghavan M, et al. Upper Palaeolithic Siberian genome reveals dual ancestry of Native Americans. Nature (2014). PMID: 24476817; PMCID: PMC4105016; DOI: 10.1038/nature13174.

- Jones ER, et al. Upper Palaeolithic genomes reveal deep roots of modern Eurasians. Nat Commun (2015). PMID: 25731166; PMCID: PMC4374627; DOI: 10.1038/ncomms7394.

- Gallego Llorente M, et al. Ancient genomes reveal the genetic structure of early Europeans. Nature (2016). PMID: 27654930; PMCID: PMC5116178; DOI: 10.1038/nature18934.

- Allentoft ME, et al. Population genomics of Bronze Age Eurasia. Nature (2015). PMID: 25731166; PMCID: PMC4374627; DOI: 10.1038/nature14238.

- Wang CC, et al. Genomic insights into the population structure of the Neolithic and Bronze Age in the Eurasian Steppe. Sci Adv (2019). PMID: 31236571; PMCID: PMC6588924; DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.aav8185.

- Narasimhan V, et al. The formation of human populations in South and Central Asia. Science (2019). PMID: 31496213; PMCID: PMC6822619; DOI: 10.1126/science.aat7487.

- Bergström A, et al. A genetic history of the North Eurasian Steppe. Nat Ecol Evol (2020). PMID: 32366952; PMCID: PMC7261338; DOI: 10.1038/s41559-020-1160-y.

- Haber M, et al. A transient pulse of Y-chromosome diversity in the Near East. Genome Res (2019). PMID: 31110093; PMCID: PMC6555819; DOI: 10.1101/gr.247197.118.

- Hallast P, et al. The Y-chromosome tree of humankind: what does it tell us about the past? Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci (2015). PMID: 26033722; PMCID: PMC4455776; DOI: 10.1098/rstb.2014.0202.

- Pagani L, et al. An Ethiopian genome reveals extensive ancient admixture with Eurasians. Science (2012). PMID: 22764349; PMCID: PMC3498024; DOI: 10.1126/science.1220616.

- Gonder MK, et al. New evidence from central Africa concerning the origin and dispersal of anatomically modern humans. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A (2007). PMID: 17592123; PMCID: PMC1941761; DOI: 10.1073/pnas.0700650104.

- Rudwick MJS. The Meaning of Fossils: Episodes in the History of Palaeontology. University of Chicago Press (1972).

- Gould SJ. Time\’s Arrow, Time\’s Cycle: Myth and Metaphor in the Discovery of Geological Time. Harvard University Press (1987).

- Albritton CC Jr. Catastrophic Episodes in Earth History. Chapman and Hall (1989).

- Clube SVM, Napier WM. The Cosmic Winter. Basil Blackwell (1990).

- Firestone RB, et al. Evidence for an extraterrestrial impact 12,900 years ago that contributed to the megafaunal extinctions and the Younger Dryas cooling. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A (2007). PMID: 17901295; PMCID: PMC2038423; DOI: 10.1073/pnas.0706970104.

- Pinter N, et al. The Younger Dryas Impact Hypothesis: A Reevaluation. Earth-Science Reviews (2011). DOI: 10.1016/j.earscirev.2011.06.005.

- Rampino MR, Stothers RB. Terrestrial mass extinctions, cometary impacts and the Sun\’s motion perpendicular to the galactic plane. Nature (1984). DOI: 10.1038/308709a0.

- Alvarez W. T. Rex and the Crater of Doom. Princeton University Press (1997).

- Koeberl C, Montanari A. The Cretaceous-Tertiary Impact Event and Other Catastrophes in Earth History. Geological Society of America (2000).

- Napier WM. Palaeolithic extinctions and the Taurid Complex. Mon Not R Astron Soc (2010). DOI: 10.1111/j.1365-2966.2010.17050.x.

- Hoyle F, Wickramasinghe C. Diseases from Space. J. M. Dent & Sons (1979).

- Davies PCW. The Fifth Miracle: The Search for the Origin of Life. Simon & Schuster (1999).

- Shaviv NJ, Veizer J. Celestial driver of Phanerozoic climate? GSA Today (2003). DOI: 10.1130/1052-5173(2003)013<4:CDOPC>2.0.CO;2.

- Svensmark H. Cosmoclimatology: a new theory emerges. Astron Geophys (2007). DOI: 10.1111/j.1468-4004.2007.4812.x.

- Landscheidt T. New Little Ice Age Instead of Global Warming? Energy & Environment (2003). DOI: 10.1260/095830503765184646.

- Easterbrook DJ. Global Cooling: The Coming New Ice Age. Cascade Enterprises (2008).

- Mörner NA, Etiope G. The Tsunami Threat: Research and Technology. Springer (2009).

- Hancock G. Fingerprints of the Gods. Crown (1995).