The End of Clocks

Authors: Sodré GB Neto, Hector Luther Honorato de Brito Siman

Lights

- Effects observed in the fall of large bolides such as “Splattion”, nuclear piezoelectricity, plasmas of very high amperages and charge differentials promote accelerated decay, altering the decay constancy, and can “age” rocks in milliseconds, falsifying radiometric dating [ 1 ] [ 2 ] [ 3 ] [ 4 ] [ 5 ] [ 6 ] [ 7 ] [ 8 ] [ 9 ] [ 10 ] [ 11 ] [ 12 ] [ 13 ] [ 14 ] [ 15 ] [ 16 ] [ 17 ] .

- Craters with larger diameters tend to have a higher apparent radiometric age (our unpublished observation);

- Larger craters are in the lower layers, following the sedimentary layers.

- Impacts on different terrains are more or less cushioned, creating greater or lesser radioactive effects.

- High radiation accelerated the entropy of living beings, creating peaks of mutation accumulation seen between 5 and 10,000 years ago.

- The magma sea on the Earth-facing side of the moon, in contrast to its heavily cratered other side, has been shown to have a strong isotopic similarity to rocks from craters that possibly ejected magmatic material to the moon.

- The complex and ultra depends on innumerable variables necessary for there to be “life”, which is only found on Earth amidst the silence in the universe, the Fermi Problem , the Great Silence [ 18 ] [ 19 ] [ 20 ] [ 21 ] [ 22 ] and silentium universi [ 22 ] [ 23 ] , therefore it did not come from space, but remnants of it were ejected from here into space, explaining more than 8,000 articles that defend panspermia based on remnants of life in meteors.

Abstract: After thousands of questionable datings of organic tissues and molecules in millions of years, which are still preserved in fossils dated by absolute dating, as being millions and even billions of years old, creating scientific controversies between young earth creationists versus academic consensus around thousands of publications trying, instead of condemning and doubting the dating methods (because they are absolute), to justify “ad hoc” the preservation of these molecules for millions of years and even billions of years; a large part of the scientific community foresaw that the scientific consensus around radiometric geochronology, considered dogmatically “absolute”, had its days numbered. Here we will be highlighting studies of the effects of the fall of large fireballs on geology and biology, addressing phenomena such as “nuclear spallation”, nuclear piezoelectricity, and giant plasmas of extremely high amperages capable of ripping off neutrons and protons, revealing the accelerated decay of materials, altering their decay constants and causing rocks to “age” in milliseconds, thus providing a scientific option to explain such organic preservations as not being millions or billions of years old, but at most a few thousand years old. We also highlight, in this context of large impacts, that a catastrophic energy event with “global magnitude” will generate other effects of global magnitude [ 24 ] [ 25 ] generating a domino effect, that is, we cannot study large geological formations without being, in blocks, much less talk about large impacts without their various immediate consequences, such as antipodal models [ 26 ] [ 27 ] [ 28 ] [ 29 ] [ 30 ] , rapid expansion of the separation of continents [ 31 ] with erosive movements creating global sedimentary layers and abrupt burial of almost all populations of ancestral living beings, still alive, transforming them into repeated fossils (paradox of morphological stasis) as fossil sampling reveals [ 32 ] [ 33 ] [ 34 ]. It is therefore necessary that geology be understood in blocks of effects and not by sectioning an isolated effect from the other consequent ones, but how can we read blocks of consequent pieces if the geochronological dating system imposes that such logical-mechanistic readings be prevented from happening? Does this geochronology, which shamefully dates organics in millions and even billions of years, now have this impeding power? As long as geochronology remains “absolute,” science becomes more of a stand-up comedy show trying to justify the miraculous preservation of organic molecules [ 35 ] [ 36 ] [ 37 ] [ 38 ] [ 39 ] [ 40 ] [ 41 ] than a conscious environment that dialogues with the reality and real age of things. Does such dating absolutism now exist in the face of so much evidence of accelerated decay and aging of rocks in milliseconds generated by large impacts? If that were not enough, we also observed, for the first time, that craters with larger diameters tend to have greater “apparent” radiometric ages, thus explaining that apparent “ages” correspond more to the nuclear effects of impacts, than to time. “Coincidentally”, the most significant and largest impacts are located in lower geological layers (what a coincidence, right?), below the sedimentary layers, and therefore will give greater ages not because they are lower in the geological column, but because these rocks have suffered more effects of decay acceleration. The high radiation resulting from these impacts accelerated the entropy of living beings, creating peaks of mutation accumulation that influenced a leap in the transformation of species, which had few mutations (mummies and fossils that were, on average, giants, and that were buried under morphological and taxonomic stasis sampling in the fossil record (burial of populations), in contrast to descendants with a very high accumulation of mutations (not explained by historical rates), on average, dwarfs, and highly modified in the current morphological and subspecies variability (without stasis except if we look at populations).

Keywords: Nuclear piezoelectricity, impacts, Vredefort, Craters, Chicxulub, Popigai, Manicouagan, Helium-3, Thorium, Decay acceleration, radiation peak, mutation peak, catastrophe, global floods, sedimentation, spontaneous segregation and stasis (SEE), Morphological Stasis Paradox, Degeneration, mutations, entropy, geochronology, isotopes, asteroid shower, late heavy bombardment, mercury, moon, antipodal, dekkan, marine trenches, Indian Ocean geoid anomaly,

Introduction

┌─────────────┐

│ Major Impacts │

└────┬────────┬────┘

│ │

┌────▼─────┐ ┌───────────────▼───────────────┐

│ Isotopic Reset │<──────┐ ┌────▶ Decay Acceleration │──▶ Mutation Peak in Living Beings Between 5 and 10,000 Years Revealed in Comparison with 5,000-Year-Old Mummies──▶ Longevity Decline Reported in Archaeology

└────┬─────┘ │ │ └────────────┬────────────────┘

│ │ │ │

▼ ▼ ▼ ▼

Spallation Plasma Piezoelectricity Isotope erosion

│ │ │ │

│

┌──────▼───────┐

│ False Ages │──▶ Probable Age between 5 and 10,000 years ago

└──────┬───────┘

▼

Blocky geology (global domino effects)

▼

Sedimentary layers are strata from the fall of a large asteroid and its fragments

▼

Horizontal layers (the trace of the sea transgressing continents) buried ancestral fossil populations of repeated morphology (morphological stasis paradox)

▼

Separation of fossils in the fossil record according to the combination of 7 aspects (1) habitat, 2) location in front of the created turbidites, 3) density and buoyancy of bodies, 4) ability to escape from sea waters 5) more continental or more marine habitat 6) ability to breathe little oxygen 7) physiological capacity to survive, thus explaining why some are higher up and others in strata lower down

▼

Long, thick, wide global sedimentary layers (Nahor NS Junior, 2009) and of common physical and chemical material segregated by SEE (Stratification stratification spontaneous www.sedimentology.fr

▼

The hypothesis of radiometric reset by catastrophic impact is strongly supported by these empirical correlations. One of the most striking challenges to the constancy of nuclear decay rates emerges from studies of piezonuclear decay, a phenomenon where mechanical forces and extreme pressures apparently alter the decay rates of radioactive elements. Research by Cardone, Mignani, and Petrucci (2009) presented experimental evidence for accelerated decay of thorium [ 42 ] under conditions of ultrasonic cavitation in aqueous solutions, a result that directly contradicts established principles of nuclear physics.

These findings are particularly relevant in the geological context, where minerals and rocks are often subjected to extreme pressures during tectonic, metamorphic or impact events. If it is proven that ordinary geological pressures can alter decay rates, this would mean that rock samples that have undergone complex pressure histories could have systematically distorted radiometric ages.

Hundreds or thousands of meteorite impacts, especially the largest ones (which are “considered” the oldest), accelerated radioactive decay, and the consequences do not represent mere “adjustments” or “corrections” to be applied, but require that the entire geochronological edifice built over decades by conventional geology be considered merely the history of science. [ 5 ] [ 6 ] [ 7 ] [ 8 ] [ 9 ] [ 10 ] [ 11 ] [ 12 ] [ 13 ] [ 14 ] [ 15 ] [ 16 ] [ 17 ]

The fundamental foundation of radiometric dating, whether by the U-Pb, K-Ar, Rb-Sr or C-14 methods, is the premise that radioactive decay rates (known as half-lives) remain absolutely constant throughout geological time and in any spatial condition. This constancy is postulated to be impervious to external factors such as temperature, pressure, electric or magnetic fields, and chemical reactions. [ 43 ]

However, studies [ 44 ] [ 45 ] [ 46 ] carried out under controlled conditions, including tests in particle accelerators, which supposedly validated the constancy of decay rates under different conditions, comparative analyses between different isotopic systems and minerals that, in theory, should produce congruent results if the decay rates were truly invariable, revealed the opposite. This well-documented physical phenomenon occurs when certain crystals, when subjected to extreme pressures, generate electrical charges on their surfaces. The magnitude of these stresses in catastrophic impact events can be sufficient to create intense local electric fields and bremsstrahlung radiation (braking radiation).

These extreme energy conditions can potentially induce two significant nuclear phenomena:

1. Nuclear transmutation – the conversion of one element into another through nuclear reactions induced by an intense electric field.

2. Temporary acceleration of radioactive decay rates – fundamentally altering the “clock” used in dating.

Different Data from Rocks “next to each other”

I still remember when I was a geology student at UFG – Universidade Federal de Goiás, when Professor Dr. Tereza Brod complained about anachronistic data of rocks next to each other, and the dating technicians condemned her methodology; she would vent this fact in class, repeating that there was no error in the methodology, because in addition to being a professor and a systematic researcher, she was the daughter of two geologists and the wife of one of the most important geologists in Brazil. Today we can perfectly understand that when we test the same rocks next to each other with very different ages, or study electric current velocities that surpass the coulomb barrier, spallation and nuclear piezoelectricity caused by impacts, forming giant plasmas due to the high charge differential, and their traction effects of nuclear decay, we understand perfectly why there was “aging” of some rocks next to another that was not affected, or had less nuclear disturbance.

Contradictions in Radiometric Dating

Such contradictions are recurrent and there are publications on the subject. As noted, “Published dates always conform to preconceived dates…” [ 47 ] Richard L. Mauger (1977) argues that dates “in the right park” are retained, while discordant ones are discarded. [ 48 ] Christopher R. C. Paul (1980) suggests that radiometric convergence is illusory due to selective exclusion. [ 49 ] Al-Ibraheemi et al. (2017) detected C-14 in dinosaur fossils ranging in age from 22,000 to 39,000 years. [ 50 ] Holdaway et al. (2018) demonstrate that magmatic carbon significantly shifts ages by C-14, as in the case of the Taupo eruption. [ 51 ] Andrew Snelling, in the RATE project, discusses divergences between dating methods and problems with fundamental assumptions. [ 52 ] George Faure, in his book, documents discrepancies between methods such as U-Pb, K-Ar and Rb-Sr. [ 53 ] A. Foscolos (2014) identifies hydrocarbon contamination as a systematic error in the C-14 method. [ 54 ] G. Brent Dalrymple (1991), despite being a defender of radiometric dating, admits to discarding inconsistent dates. [ 55 ] but many do not declare this due to lack of knowledge or fear of going against the consensus, and having to face retaliation from the priests of the Darwinist ideological doctrine that, as a substitute religion (Darwinism depends heavily on millions of years to explain the “creation” of all living beings), dominates with an iron pen and persecutions of “heretical” scientists, since Darwin, in academia to this day [ 56 ] . Elaine Howard Ecklund and Christopher P. Scheitle, who analyze the difficulties faced by religious academics in the United States, highlighting cases of marginalization and stigmatization [ 57 ] . In addition, the discussion on how prejudices against religious beliefs affect inclusion and the academic environment is addressed in the article published in the *Journal of Diversity in Higher Education*, which discusses the impact of religious discrimination [ 58 ] . The experience of religious students in secular universities is evidenced in a qualitative study that reveals the perceptions of these students in predominantly secular environments [ 59 ].Finally, a reflection on religious diversity and the challenges of tolerance in the university environment is explored by Michael J. Perry, who discusses the relevance of religion in academia and the associated challenges [ 60 ] . Scientific articles on scientists persecuted for their religious convictions address the challenges that these individuals have faced throughout history. An important study is by Peter Harrison, who analyzes the historical relationship between science and religion, discussing cases of persecution of scientists for their opinions [ 61 ] . Another relevant article is by Edward Grant, who explores how religious convictions influenced the lives of scientists during the Scientific Revolution and the challenges they face [ 62 ] . Discrimination and the challenges faced by religious scientists in academic environments are investigated by Elaine Howard Ecklund and Christopher P. Scheitle, who discuss the struggle between faith and science [ 63 ] . Finally, Michael Ruse discusses how the personal influences of scientists can influence their research and the repercussions that their own convictions have [ 64 ] . Add prejudice when religious people defend creationism, they will have to face a ton of articles and criticism. [ 65 ] [ 66 ] [ 67 ] [ 68 ] In this context, we can calculate the controversial and intolerant weight will be to question data, preservation of organic tissues, consider sedimentary layers as strata of catastrophes related to global floods, fine-tuning, genetic entropy, irreducible complexity, etc. [ 69 ] [ 70 ] [ 71 ] [ 72 ]

Impacts and GeochronologySummary Table of Mechanisms

| Mechanism | Description |

|---|---|

| Isotopic Reset | Erases/distorts the isotopic memory of zircon and titanite. |

| Plasma and Extreme Pressure | Thermal and electrical changes that reconfigure geochronological systems. |

| Fake Age Signatures | Apparent ages altered by intense recrystallization. |

| Emblematic Cases | Chicxulub, Sudbury and Vredefort as examples of radical geological modifications. |

Fireball Impacts and Geochronology

When a large bolide (meteor, asteroid, etc.) impacts the Earth, it releases a colossal amount of energy in a short period of time, generating extreme physical and chemical conditions, such as pressure in the order of gigapascals and temperatures that can exceed thousands of degrees Celsius. These conditions include ionization characteristics, plasma formation, and intense electric and magnetic fields. And even if one or more extinctions had other causes, the largest asteroid/comet impacts before (larger) and during the Phanerozoic cannot avoid having sedimentary layers left and being directly responsible not only for the extinction of the dinosaurs as is repeated, but for almost the entire fossil record. [ 73 ]

Isotopic Effects and Apparent “Rejuvenation/Aging”

Radiometric methods, such as U-Pb (Uranium-Lead) and K-Ar (Potassium-Argon), measure the decay of radioactive isotopes over time. A violent impact can:

- Reset the geological “clock” by melting minerals and resetting isotopic systems.

- Chaotically reconfigure isotopes and mineral phases, leading to misleading age readings that are much older or younger.

For example, zircon, a common mineral in U-Pb dating, can:

- Partially melt.

- Lose radiogenic lead.

- Create zones with drastic age differences apparent in milliseconds. [ 1 ]

Piezoelectricity and Massive Loads

Minerals such as quartz are piezoelectric. Sudden pressures generate intense electric fields, which can:

- Generate plasma by ionizing air and soil.

- Produce gigantic electrostatic discharges.

- Cause chemical and crystal structure changes in nanoseconds.

Giant Plasmas and Local Transmutation

Plasma can reach temperatures of millions of Kelvin for a brief instant. Although speculative, there are controversial hypotheses that this may cause local transmutation of elements, changing isotopic ratios and, consequently, apparent ages.

Instant Aging

A large-bolide impact can “age” a rock in milliseconds. If a post-impact rock has isotopes that show it is 1 billion years old, but the event occurred milliseconds ago, the impact created a misleading isotopic signature, what some call “flash aging.”

Scientific Conclusion

A large bolide impact can “age” a rock within milliseconds by altering its isotopic and structural signatures. Mechanisms include:

- Sudden melting.

- Chaotic recrystallization.

- Loss/addition of isotopes.

- Electrical/plasma modifications.

- Speculative local nuclear effects.

Emblematic Cases

The Chicxulub, Sudbury and Vredefort craters are prime examples of how geology can be radically altered by catastrophic events. Studies of these sites show how impacts can affect geochronology and the interpretation of geological ages. [ 4 ] [ 2 ]

Asteroid Rain on Earth

The idea that Earth experienced an intense shower of large asteroids (NEOs) in the past, especially during periods such as the Precambrian and Paleozoic, is supported by several lines of geological and astronomical evidence.

- Fragmentation and cascading: Studies show that large parent bodies in the asteroid belt can fragment due to catastrophic collisions, producing a flood of smaller fragments that can cross Earth’s orbit. Bottke et al. (2005) discuss the origin of NEOs from fragmented asteroid families, indicating that mass fragmentation events are the dominant source of these near-Earth objects. [ 74 ]

- Decreasing rate of recent impacts: The oldest impact crater on Earth, dated to about 2 billion years ago, and the highest concentration of astroblemes in ancient rocks (Precambrian and Paleozoic) are evidence that the frequency of large impacts has decreased over time. This is consistent with dynamic modeling of the NEO population, which suggests that the largest bodies broke up and were gradually removed from near-Earth orbit. [ 75 ] [ 76 ]

- Current number of NEOs: Estimates indicate that there are about 25,000 to 30,000 NEOs larger than 140 meters (Mainzer et al., 2011; NASA NEO Survey). The reduction in the number of large remaining bodies supports the idea of a much larger initial population that was gradually eliminated by impacts and gravitational interactions, corroborating the hypothesis of past asteroid showers. [ 77 ]

The hypothesis of an intense rain of larger asteroids during the Earth’s earliest eras (Precambrian and Sedimentary) explains the high density of astroblemes from those epochs, as well as the discrepancy between the current number of NEOs and the geological record of impacts.

- Astroblems and the geological record: Grieve (1991) points out that the preservation of ancient craters is strongly influenced by tectonic and erosional processes, but the high number of craters in ancient rocks indicates a higher rate of impacts in the past. [ 78 ]

- Fragmentação e origem dos NEOs: Bottke et al. (2002) e Morbidelli et al. (2002) argumentam que a fragmentação de asteroides e a subsequente dispersão dos fragmentos fornecem a origem mais plausível para a população atual de NEOs, explicando a presença contínua de pequenos corpos próximos da Terra.[79][80]

- Implicações para a evolução planetária: A chuva de asteroides teria tido impactos significativos na evolução da Terra, influenciando desde a composição da crosta até eventos de extinção em massa.

34 autores liderados pelo Dr. Edward J. Steele, apresenta um bombardeio de asteroides como causa da “explosão” cambriana; bem como considera bombardeamento de bólidos como estando presentes nos principais pontos de mudança geológico-evolucionaria da terra[81][82]. Considerando a hipótese de que a Terra tenha sido submetida a um intenso cenário de chuva de asteroides, respaldado por evidências substanciais publicadas[83][84] e chamadas de chuva de asteroides ou bombardeio intenso tardio (Late Heavy Bombardment, LHB)[85][86], asteroides binários[87] , bombardeamento de asteroides[88], múltiplos impactos[89][90][91], quais implicações poderíamos extrair para a compreensão da história geocronológica[92], sedimentar[93], paleontológica e genética? Primeiro devemos considerar que a queda de grandes asteroides teria gerado um atrito colossal e efeitos como a “spallação”, capazes de produzir isótopos radioativos nas rochas. Este fenômeno, aliado a fatores como piezoeletricidade nuclear[44][45][46], temperaturas instantâneas extremas, ondas sonoras e diferenciais de carga, resultou na formação de plasmas gigantes de alta velocidade de elétrons capaz de cortar a crosta continental em milisegundos. Esta elevada amperagem gerou elétrons em velocidades que ultrapassaram a barreira de Coulomb, promovendo a rápida decaída de nêutrons[94] e prótons, tanto de elementos pesados quanto leves, criando um ambiente de intensa radiação e calor que impactou todos os seres vivos. Além disso, os plasmas gerados pelos impactos de asteroides, advindos pela alta amperagem gerada pelo diferencial de cargas produzidos pelos grandes efeitos de atrito, piezoeletricidade e variações térmicas, contestam a premissa da “constância” do decaimento radioativo explicando, entre outros efeitos, a abundancia de Torio e Helio-3 nas crateras [95][96][97][98][99][100], constância esta que fundamenta as datações radiométricas. Essa nova perspectiva transforma a compreensão da cronologia geológica e histórica pois os grandes eventos de impacto produzem quantidade de Hélio-3 e Torio. Estudos detalhados de vidros de impacto associados a crateras como Chicxulub (México, ~180 km), Popigai (Rússia, ~100 km) e Manicouagan (Canadá, ~100 km) revelaram concentrações de Hélio-3 significativamente acima dos níveis de fundo terrestres, frequentemente por ordens de magnitude.

Impactos Terrestres e suas Consequências

Uma hipótese[101] do Dr. Robert Kutz, baseada em impacto, propos que a depressão amazônica é resultado de deformação tectônica na intersecção de ondas de choque sísmicas originadas de dois grandes impactos planetários: o impacto de Chicxulub na Península de Yucatán (~66 Ma) e um impacto hipotético anterior próximo à Fossa das Marianas. O trabalho explora a possibilidade de amplificação antipodal em larga escala de energia sísmica e efeitos de interferência como mecanismos para deformação em escala continental. Usando ferramentas de geoinformática (ArcGIS, GPlates), dados topográficos e gravimétricos (SRTM, GEBCO, GRACE), e análogos planetários comparativos (Marte, Mercúrio, Lua), o estudo delineia um modelo geodinâmico sintético explicando a origem da bacia Amazônica como uma geoestrutura pós-impacto. Ormö et al. (2014)[102] documentam o primeiro impacto conhecido de um asteroide binário na Terra, evidenciando efeitos geológicos significativos. A análise de Hassler e Simonson (2001)[103] sobre registros sedimentares de impactos extraterrestres fornece evidências de eventos antigos. Glikson et al. (2004)[104] revelam múltiplas unidades de apocalipse de impactos antigos de impactos antigos, enquanto Heck et al. (2017)[105] investigam meteoritos raros comuns no período Ordoviciano. As camadas estraticadas em plano paralelo[106][107][108] refletem aprofundamento e demonstrações laboratoriais de Nicolas Steno[109] que remetem a modelos catastrofistas para a formação rápida das camadas[110] sedimentares[110][111] , muitas formadas por consequências de astroblemas, asteroides binários[87] , bombardeamento de asteroides[88], múltiplos impactos[89][90][91] , abrangência de sedimentação gerado por impactos verificado por padrão de micro-esférulas semelhantes em um terço do planeta[112], “queda catastrófica do nível de oxigênio, que é conhecido por ser uma causa de extinção em massa”[113][114], deriva continental causado por impacto[115][116][117]. Schmitz e Bowring (2001)[118] analisam como impactos extraterrestres[119] influenciaram a evolução geológica do planeta. Reimold e Gibson (1996)[120] fazem uma revisão abrangente da evidência geológica de cráteres de impacto. Bottke et al. [121] discutem as origens dos asteroides e suas implicações para chuvas de impactos[122][123][124][125]. A teoria da chuva de asteroides ou bombardeio intenso tardio (Late Heavy Bombardment, LHB) postula que a Terra e outros corpos do sistema solar interno sofreram uma grande quantidade de impactos de asteroides e cometas. Ironicamente não atentam para os efeitos radioativos destas quedas invalidando totalmente datações de relogios radiométricos baseados em taxas constantes entre 4,1 e 3,8 bilhões de anos atrás, bem como relogios de taxas mitocondriais devido ao pico acentuado entre 5.000 anos e a atualidade, logo após a diferenciação de mutações mitocondriais destacado nas 3 primeiras Ls matriarcais em franca acenção sob taxcas de acúmulo altíssimas como revela os gráficos abaixo:

Atrito e Geração de Calor

Do ponto de vista da física nuclear e atmosférica, a entrada de um grande asteroide na atmosfera terrestre desencadeia uma sequência intensa de processos termodinâmicos, eletromagnéticos e nucleares, conforme descrito por estudos como o de Schuch (1991[126]). Na “Introdução ao estudo dos raios cósmicos e sua interação com a atmosfera terrestre.”é citado que as medições teóricas e simulações indicam que esse processo pode gerar campos elétricos intensos na ordem de 10⁶ V/m, criando um potencial elétrico massivo ao redor do corpo celeste.[127][128]

Ao penetrar a atmosfera a velocidades superiores a 11 km/s, o asteroide sofre intenso atrito com as camadas atmosféricas[129], levando à compressão adiabática do ar em sua frente de choque. Este processo é caracterizado por uma transformação extremamente rápida da energia cinética em energia térmica, criando condições físicas raramente observadas na natureza[130].

O atrito gera um aquecimento extremo (>3000 K), suficiente para vaporizar parcialmente a superfície do próprio asteroide. Essa temperatura elevada provoca a ionização de gases atmosféricos, formando uma concha de plasma condutor ao redor do objeto que altera significativamente suas propriedades aerodinâmicas e eletromagnéticas.

At the same time, a hypersonic pressure envelope is formed, further intensifying friction and drag. This phenomenon is similar to that observed during space capsule reentries, but on a much larger scale and with potentially catastrophic consequences for the impact region.

During the impact of a large bolide, a separation of electrical charges is formed between the highly ionized plasma and the non-conductive rocky crust of the asteroid. This can generate:

- Intense electric fields (~10⁶ V/m);

- Transient currents of very high magnitude (order of mega-amperes);

- Internal atmospheric lightning-like discharges, similar to sprites and blue jets, but with hundreds of times more energy.

- Nuclear Spallation and Neutron/Proton Emission

At the point of impact with the ground or at very low altitudes (air impact), high-energy particles and the relativistic shock generate:

- Nuclear spallation: atmospheric nuclei are bombarded by high-energy particles, releasing free neutrons and protons [ 131 ] ;

- Formation of secondary particles: muons, pions and gamma radiation, as shown in atmospheric cosmic ray cascades.

The friction generated during the impact of an asteroid represents one of the most energetic aspects of this phenomenon. When a celestial body hits the Earth’s surface at hypersonic speeds, the friction resulting from the interaction between the projectile and the target material produces extreme heating, which can reach temperatures above 10,000°C in a matter of milliseconds.

This heating process is not limited to the point of impact. Thermal energy propagates radially through the ground, creating concentric zones of thermal metamorphism. In regions closest to the epicenter, the heat is sufficient to instantly vaporize rocks and minerals [ 132 ] , transforming them into a high-temperature plasma. In intermediate zones, partial or complete melting of the rock material occurs, while more distant areas experience recrystallization and other mineralogical changes due to thermal shock.

According to studies by Zhang et al. (2008), this extreme friction also contributes to the acceleration of electrons to high energies, creating conditions for nuclear reactions in the impacted rocks. The heat generated by friction causes the excitation of electrons in the atoms, resulting in ionization and, in extreme cases, the breaking of nuclear bonds.

The thermal effects of an impact persist for varying lengths of time, depending on the magnitude of the event. Large impacts can create thermal anomalies that persist for decades or even centuries, significantly altering regional and global climate patterns. This prolonged warming has direct implications for the survival of species in the affected areas and can trigger cascading effects on terrestrial ecosystems.

It has been argued that the impacts should be exceptionally more lethal globally than any other proposed terrestrial causes of mass extinctions due to two unique features: (a) their environmental effects happen essentially instantaneously (on timescales of hours to months, during which species have little time to evolve or migrate to sheltered locations), and (b) there are compounding environmental consequences (e.g., grilling skies as ejecta reenter the atmosphere, global fire, ozone layer destruction, earthquakes and tsunamis, months of subsequent “impact winter”, centuries of global warming, ocean poisoning). Not only the rapidity of the changes, but also the cumulative and synergistic consequences of the compounding effects, make an asteroid impact overwhelmingly more difficult for species to survive than alternative crises. Volcanism, sea regressions, and even sudden effects from hypothetical collapses of continental shelves or ice caps are much less abrupt than the immediate (within a few hours) worldwide consequences of an impact; life forms have much better opportunities in longer-duration scenarios to hide, migrate, or evolve.

Immediate Temperature and Thermal Effects

The instantaneous temperature increase represents one of the most devastating aspects of asteroid impacts. At the moment of impact, the kinetic energy of the asteroid is converted primarily into thermal energy, generating temperatures that can exceed tens of thousands of degrees Celsius at the point of impact – values comparable to the surface of the Sun (Collins et al., 2005; Wünnemann et al., 2008). During the impact of a large bolide, extreme temperatures are reached almost instantaneously, often exceeding several thousand degrees Celsius. As noted in the studies of Melosh (1989 [ 133 ] ) and French (1998), these conditions are sufficient to cause melting and vaporization of target rocks, creating an environment where matter exists in extreme states rarely observed on Earth.

This extreme heat instantly vaporizes both the asteroid and the rocks at the point of impact, creating a rapidly expanding cloud of superheated vapor. The vaporized rocky material can reach temperatures of 8,000 to 10,000°C, forming a rising plume that rises into the atmosphere (Artemieva & Morgan, 2009; Johnson & Melosh, 2012). When this material cools and condenses, it can precipitate as small glass spheres (microtektites) or angular fragments that are distributed globally in large-magnitude events (Glass & Simonson, 2013).

A radiação térmica emitida pela pluma e pelos materiais ejetados pode causar incêndios em áreas extremamente distantes do ponto de impacto. No caso do impacto de Chicxulub[134][135], que causou a extinção também dos dinossauros, evidências sugerem que incêndios florestais em escala global foram desencadeados pela radiação térmica intensa que atingiu a superfície terrestre quando os fragmentos ejetados reentram na atmosfera, criando um fenômeno conhecido como “chuva de meteoros secundária” (Robertson et al., 2013; Bardeen et al., 2017).

O aquecimento atmosférico global que segue grandes impactos pode persistir por semanas ou meses. Este efeito estufa temporário mas intenso tem consequências profundas para os ecossistemas terrestres, especialmente para organismos sensíveis a variações de temperatura. Estudos de Melosh (1989) demonstram que, para impactos de magnitude suficiente, a temperatura da superfície terrestre pode aumentar o suficiente para causar a fervura dos oceanos superficiais, criando condições absolutamente incompatíveis com a maioria das formas de vida conhecidas. Pesquisas mais recentes de Toon et al. (2016) e Artemieva & Shuvalov (2016) confirmaram estes efeitos térmicos catastróficos usando modelos computacionais avançados de hidrodinâmica.

Processos de Fusão Nuclear em Impactos

Um dos aspectos mais controversos e fascinantes da física de impactos de asteroides é a possibilidade de ocorrência de processos de fusão nuclear em pequena escala. A fusão nuclear, o mesmo processo que alimenta as estrelas, requer condições extremas de temperatura e pressão para superar a repulsão eletrostática entre núcleos atômicos e permitir que se fundam, liberando energia, a constância do decaimento radioativo é fundamental para a datação, mas fatores externos podem influenciar esses processos (Hu et al., 2015). Eventos cósmicos como chuvas de asteroides podem afetar a estabilidade isotópica (Tanaka et al., 2019). (Crawford & Schultz, 2014; Boslough & Crawford, 2008).[136][137][138][139]

Durante o impacto de grandes asteroides, as temperaturas no ponto de colisão podem atingir dezenas de milhares de graus Celsius, aproximando-se das condições encontradas na superfície do Sol. Simultaneamente, as pressões instantâneas podem exceder milhões de atmosferas (Melosh & Collins, 2019;[140] Pierazzo & Artemieva, 2012[141]). Nestas condições, particularmente no plasma de alta energia gerado pelo impacto, íons de elementos leves como hidrogênio, deutério e trítio podem ocasionalmente se aproximar o suficiente para que a força nuclear forte supere a repulsão eletrostática, resultando em fusão (Svetsov & Shuvalov, 2016[142]; Tagle & Hecht, 2006[143]).

Evidências indiretas de possíveis processos de fusão durante impactos podem ser encontradas na análise de isótopos anômalos em rochas impactadas. Por exemplo, concentrações incomuns de hélio-3, um produto típico de certas reações de fusão, têm sido identificadas em vidros de impacto (tectitos) (Koeberl et al., 2018[144]; Simonson & Glass, 2004[145]). Além disso, a presença de elementos leves com razões isotópicas alteradas poderia ser explicada por processos limitados de fusão nuclear (Qin & Humayun, 2020; Jourdan et al., 2012; Osinski & Pierazzo, 2013[146]).

É importante ressaltar que, se ocorrer, a fusão nuclear durante impactos seria um fenômeno localizado e de curta duração, não comparável em escala às reações contínuas que ocorrem no interior do Sol (Johnson & Melosh, 2022; French & Koeberl, 2010). No entanto, mesmo processos limitados de fusão contribuiriam para o inventário total de energia liberada durante o impacto e poderiam produzir assinaturas geoquímicas distintas que auxiliam os cientistas na identificação de antigos locais de impacto (Glass & Simonson, 2017; Reimold & Koeberl, 2014[147]; Wünnemann et al., 2016).

Formação de Plasma em Grandes Impactos

One of the most spectacular and energetic phenomena resulting from the impact of large asteroids is the formation of plasma [ 148 ] [ 149 ] [ 150 ] [ 151 ] [ 152 ] [ 153 ] [ 154 ] – a highly ionized state of matter composed of free electrons and positive ions. This fourth state of matter forms when extreme temperatures and intense electric fields cause electrons to separate from their atoms, creating a conductive gas that can interact strongly with electromagnetic fields.

In the first moments after impact, the combination of temperatures that can exceed tens of thousands of degrees Celsius, electric fields generated by piezoelectric effects, and the intense pressure of the shock wave create ideal conditions for the mass ionization of the vaporized material. The resulting plasma can extend for several kilometers above the point of impact, forming a column of light visible at great distances.

The physics of this impact plasma is extremely complex. Due to the high amperage – which can reach millions of amperes – massive electrical currents flow through the plasma, generating intense magnetic fields. These fields, in turn, can confine and direct the plasma, creating filamentary structures and vortices. Massive lightning can be observed in this phase, as a result of the differences in electrical potential and the high conductivity of the ionized medium.

A particularly significant aspect of this phenomenon is that, within the plasma, electrons can be accelerated to relativistic speeds. As highlighted by Zhang et al. (2008), these energetic particles can reach energies sufficient to overcome the Coulomb barrier – the electrostatic repulsion force between particles of the same charge – allowing interactions with atomic nuclei that would normally be energetically unfavorable. This mechanism facilitates both nuclear spallation and, potentially, small-scale nuclear fusion processes.

Nuclear Spallation in Asteroid Impacts

- Spallation Products: Light isotopes such as beryllium-10, carbon-14, and chlorine-36 produced by spallation reactions during impact.

- Perturbed Isotope Ratios: Isotopic systems such as Sm-Nd, Rb-Sr and U-Pb that show characteristic perturbations caused by the extreme conditions of the impact.

Nuclear spallation is one of the most fascinating and least understood phenomena associated with asteroid impacts. This process occurs when high-energy particles generated during the impact collide with atomic nuclei in rocks, fragmenting them and releasing neutrons, protons, and alpha particles. The result is the production of radioactive isotopes that would not normally be abundant in the Earth’s crust.

During a high-energy impact, electrons are accelerated to relativistic speeds due to the immense electromagnetic field generated. These energetic electrons, when interacting with the nuclei of atoms present in the rocks, trigger nuclear reactions that alter the isotopic composition of the elements. As indicated by Zhang et al. (2008), this acceleration of electrons during asteroid impacts can reach energies sufficient to induce significant nuclear reactions.

Radioactive isotopes formed by spallation act as “geological clocks,” allowing scientists to date impact events with considerable precision. Elements such as beryllium-10, aluminum-26, and chlorine-36 are particularly important in this context because their half-lives are known and their anomalous presence in rocks may indicate exposure to spallation events.

In addition to their value as time markers, radioactive isotopes produced by spallation also contribute to increased local radiation after impact. This increased radiation can persist for prolonged periods, depending on the half-lives of the isotopes formed, and represents an additional stressor for surviving organisms in the impact-affected areas.

Overcoming the Coulomb Barrier

The Coulomb barrier represents one of the fundamental principles of nuclear physics, consisting of the electrostatic repulsion force that prevents positively charged atomic nuclei from getting close enough for nuclear reactions to occur. Under normal conditions, this barrier acts as a protective shield that maintains the stability of atoms, requiring extremely high energies to be overcome.

During large asteroid impacts, however, extraordinary conditions allow this barrier to be temporarily overcome. Electrons accelerated in the high-energy plasma generated by the impact can reach speeds close to the speed of light. When these relativistic electrons collide with atomic nuclei, they can transfer enough energy to temporarily compress the electron cloud, effectively reducing the distance between neighboring nuclei.

Furthermore, the extremely high temperatures and pressures resulting from the impact provide additional thermal energy to the nuclei, increasing the likelihood of quantum tunneling through the Coulomb barrier. This phenomenon, known as the tunneling effect, allows particles with insufficient energy to overcome an energy barrier to still pass through it, thanks to the principles of quantum mechanics.

The overcoming of the Coulomb barrier in impact environments has profound implications for the geochemistry of the affected rocks. It allows the accelerated decay of unstable isotopes and facilitates nuclear transmutation reactions, where one element can be converted into another. These nuclear transformations contribute to the formation of rare isotopes and elements that would not normally be found in the concentrations observed in impacted rocks, providing a unique geochemical signature of these catastrophic events.

The Coulomb barrier represents the energy required for nuclear interactions. Overcoming this barrier is essential in fusion reactions (Bertsch et al., 2014). Electron acceleration can be facilitated by temperature and sound waves (McCoy et al., 2013).

Accelerated Decay of Neutrons and Protons

One of the most extraordinary phenomena associated with large asteroid impacts is the accelerated decay of subatomic particles, particularly neutrons and protons. Under normal conditions, protons are extremely stable (with a theoretical half-life exceeding the age of the universe), while free neutrons have a half-life of approximately 15 minutes before decaying into a proton, an electron, and an antineutrino.

In the high-energy environment created by an asteroid impact, the conventional rules of nuclear physics are temporarily altered. The intense electromagnetic forces generated in the impact plasma can destabilize subatomic particles, both light and heavy elements. Neutrons can be ejected from nuclei through spallation reactions and, once free, their decay can be significantly accelerated by the extreme conditions present.

This accelerated decay has several important consequences. First, it contributes to the release of additional energy in the form of beta radiation (high-energy electrons) and gamma rays. Second, it alters the isotopic composition of the impacted rocks, creating anomalous isotopic ratios that can be detected even billions of years after the event. Third, the resulting nuclear transmutation can produce rare elements and isotopes, some of which are radioactive with variable half-lives.

Evidence of this process can be found in detailed analysis of impacted rocks. Abnormal concentrations of certain isotopes, such as helium-3, beryllium-10 or neon-21, are often interpreted as evidence of impact-induced nuclear reactions. These isotopic anomalies constitute a nuclear “fingerprint” that allows geoscientists to identify and date ancient impact events, even when other morphological evidence has been eroded by time.

Radiation Emission During Impacts and Piezoelectric Effect in Impacted Rocks

O efeito piezoelétrico, embora frequentemente associado a cristais como quartzo em aplicações tecnológicas, desempenha um papel significativo durante impactos de asteroides. Este fenômeno ocorre quando certos minerais, principalmente silicatos como quartzo e feldspato, geram uma diferença de potencial elétrico em resposta à deformação mecânica extrema causada pelo impacto[155].

Quando as ondas de choque do impacto se propagam através da crosta terrestre[156], exercem pressões instantâneas enormes sobre os cristais rochosos. Nos minerais piezoelétricos, essa compressão força um realinhamento das cargas elétricas internas, criando momentaneamente campos elétricos localizados de alta intensidade. Em rochas ricas em quartzo, como granitos e arenitos, esse efeito pode ser particularmente pronunciado, gerando diferenças de potencial da ordem de milhares de volts.

A emissão de radiação durante eventos de impacto de asteroides representa um aspecto crítico tanto para a compreensão da física desses fenômenos quanto para a avaliação de seus efeitos biológicos. Quando um grande asteroide colide com a Terra, múltiplos mecanismos contribuem para a liberação de diferentes tipos de radiação ionizante e não ionizante, criando um ambiente temporariamente hostil à vida.

A radiação térmica constitui a primeira e mais óbvia forma de emissão. O calor intenso gerado pelo impacto produz radiação infravermelha e luz visível em quantidades massivas, potencialmente causando incêndios em áreas distantes do epicentro. Para impactos verdadeiramente grandes, como o evento K-T de 65 milhões de anos atrás, estima-se que a radiação térmica tenha sido suficiente para aquecer a atmosfera global a temperaturas próximas de 100°C por várias horas.

A radiação ionizante, incluindo raios X, raios gama e partículas de alta energia (prótons, nêutrons e elétrons), é produzida através de vários processos nucleares já mencionados: spallação, decaimento acelerado e, em casos extremos, possíveis reações de fusão em pequena escala dentro do plasma de impacto. Essa radiação ionizante penetra profundamente em materiais orgânicos, danificando DNA e proteínas, e pode ser particularmente letal para organismos complexos.[157][158][159][160][161][162][163][164][165]

These transient electric fields contribute to the ionization of air and vaporized materials, facilitating the formation of plasmas. In addition, they can interact with the magnetic fields generated by the movement of conductive material during impact, creating complex electromagnetic interactions. The piezoelectric effect can also accelerate charged particles, especially electrons, amplifying the spallation processes already mentioned.

The implications of this phenomenon go beyond the immediate physics of the impact. Piezoelectrically generated electric fields can induce unconventional chemical reactions in impacted rocks, contributing to the formation of minerals and compounds that would not normally form under standard geological conditions. These mineralogical anomalies serve as important geochemical signatures that allow scientists to identify ancient impact sites even when the crater morphology has already been eroded.

Humanity had a peak accumulation of deleterious genes between 5 and 10,000 years ago and more precisely between 2 and 6,000 years ago.

This Nature article cited in Crabtree’s thesis on our fragile intellect [ 166 ] and the prediction of an exponential increase in neurological diseases, shows us that there was a beginning of accumulation of deleterious genes between 5 and 10,000 years ago, in a true explosion of them [ 167 ] , as revealed in this published study [ 168 ] :

“Large-scale studies of human genetic variation have reported signatures of recent explosive population growth, notable for an excess of rare genetic variants, suggesting that many mutations have arisen recently. To further quantitatively assess the distribution of mutation ages, we resequenced 15,336 genes in 6,515 individuals of European American and African ancestry and inferred the ages of 1,146,401 autosomal single nucleotide variants (SNVs). We estimate that approximately 73% of all protein-coding SNVs and approximately 86% of SNVs predicted to be deleterious arose in the last 5,000–10,000 years. The mean age of deleterious SNVs varied significantly across molecular pathways, and disease genes contained a significantly higher proportion of recently arisen deleterious SNVs from other genes. Furthermore, European Americans had an excess of deleterious variants in essential and Mendelian disease genes compared with European Americans. African Americans, according to weak purifying selection, due to Out-of-Africa dispersal.”

Today, we have a second BLAST database with between 15 and 88 million mutations with “a broad spectrum of genetic variation, in total, more than 88 million variants (84.7 million single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), 3.6 million short insertions/deletions (indels) and 60,000 structural variants.” [ 169 ] [ 170 ] [ 171 ] [ 172 ] in 100,000 germline genes [ 173 ] . If we have an accumulation of 150 deleterious mutations every 25 years (generation), it is easy to measure when we approximately had genetic purity [ 174 ] . A very interesting fact was summarized by Dr. Marcos Eberlin [ 175 ] , combining the mutational rates and perceived peaks, which accumulate generation after generation, and then dividing by generation in relation to the total mutations identified in the human genome [ 176 ] [ 177 ] . We discovered that just 6 to 12,000 years ago, or around 10,000 years ago [ 178 ] we had genetic purity [ 179 ] , that is, this confirms the archaeological biblical account of Genesis when it speaks of the initial ancestors Adam and Eve [ 180 ] [ 181 ] , as well as confirming statistical genealogies around 6,000 years as the temporal distance of the ancestral patriarchs of humanity [ 182 ] [ 183 ] [ 184 ] [ 185 ] [ 186 ] [ 187 ] [ 188 ] [ 189 ] [ 190 ] being that, since 2004, it was already admitted that of those currently alive, “the MRCA (most recent common ancestor) of all current humans lived only a few thousand years ago. [ 191 ] and that the living and the dead could not be so far apart.

The Contrast of Fossils in Morphological Stasis with Current Biodiversity Reveals a Catastrophe that Modified an Environment that Existed on the Planet

A mudança drástica no ser vivo indica mudança drástica de ambiente[192][193][194]. Não temos gigantes sendo produzidos pela evolução hoje, hoje, as poucas exceções das baleias e girafas estão em extinção, mas no registro fóssil os gigantes são abundantes[195][196][197][198][199] . A mudança de ambiente pressiona os seres vivos a se adaptarem, variarem, e consequentemente empobrecerem geneticamente, uma destas mudanças pode estar ligada a riqueza genética das espécies mães, e a atmosfera do planeta Terra, que detinha maior concentração de oxigênio, o que favorecia ainda mais as formas de vida, longevidade , tamanho, e maior comensalidade de microorganismos como vírus, bactérias e fungos . A oxigenação é fartamente citada na literatura como gerando múltiplos efeitos benéficos a saúde e diversas técnicas tem sido defendidas como ferramentas úteis nos tratamentos como câmaras hiperbáricas, ventiladores, balão de oxigênio e ozonioterapias[200]. O prefeito de Itajaí- SC, Brasil, médico, Dr. Volnei Morastoni, tem recomendado a aplicação retal de ozônio para pacientes que apresentem sintomas do novo coronavírus SARS-CoV-2 que manifesta Covid-19. Alguns ensaios clínicos tem sido publicados confirmando a eficiência desta técnica centenária para Covid-19[201] [202]. A técnica já conta mais de 3500 artigos no Pubmed e mais de 8000 artigos no Science Direct e desde a patente de Tesla em 1896 que se sabe dos múltiplos benefícios da ozonioterapia atuando no combate a 264 doenças incluindo efeitos antivirais, oxigenação, aspectos antinflamatórios e antidiabéticos[203][204][205], melhorando a circulação, combatendo hipertensão[206], grávidas hipertensas[207], doenças de pele[208] o que coloca a técnica como conversora de inúmeros benefícios conjuntos aos pacientes de risco, tantos, que ameaçam centenas de patentes de medicamentos, provocando perseguições de agencias do governo, e midia, muitas vezes controladas por lobbys da industria farmacêutica. Neste contexto dos benefícios do oxigênio, percebemos que a terra era ainda mais adaptável a vida , ainda mais bem projetada, e na sua falta, temos o aumento da entropia genética nas suas formas EGI e EGP (Entropia genética individual no envelhecimento e populacional no acúmulo de mutações genéticas germinativas).

The discrepancy in mutation rates can be interpreted in light of the theory that catastrophic events induce mutation spikes. Radiation, as a mutagenic agent, can explain the observed increase in modern mutations compared to ancient ones. The erroneously called “natural selection” when there is nothing selecting, can act on these mutations, favoring the survival of those that confer adaptive advantages in altered environments [ 209 ] . However, these “advantages” are generally degenerative, as resistant bacteria that have been simplified, losing receptors and therefore can no longer receive antibiotics, are therefore called resistant. In addition, the accumulation of these deleterious resistant mutations leads to genetic degeneration, increased susceptibility to diseases, impoverishment of the gene pool by the elimination of non-“resistant” ones and the consequent increase in the frequency of the same deleterious alleles.

Mutation Peaks in Catastrophes: A Response to the Divergence Between Historical and Modern Rates of Mitochondrial Mutations

The discrepancy between mitochondrial mutation accumulation rates estimated from ancient and modern data represents a puzzle in evolutionary biology. This paper proposes that catastrophic events, particularly those associated with intense radiation and severe environmental stress, induce mutation peaks that explain this discrepancy. Furthermore, it explores the implications of these mutation peaks for human degeneration and the accumulation of deleterious mutations in the human genome.

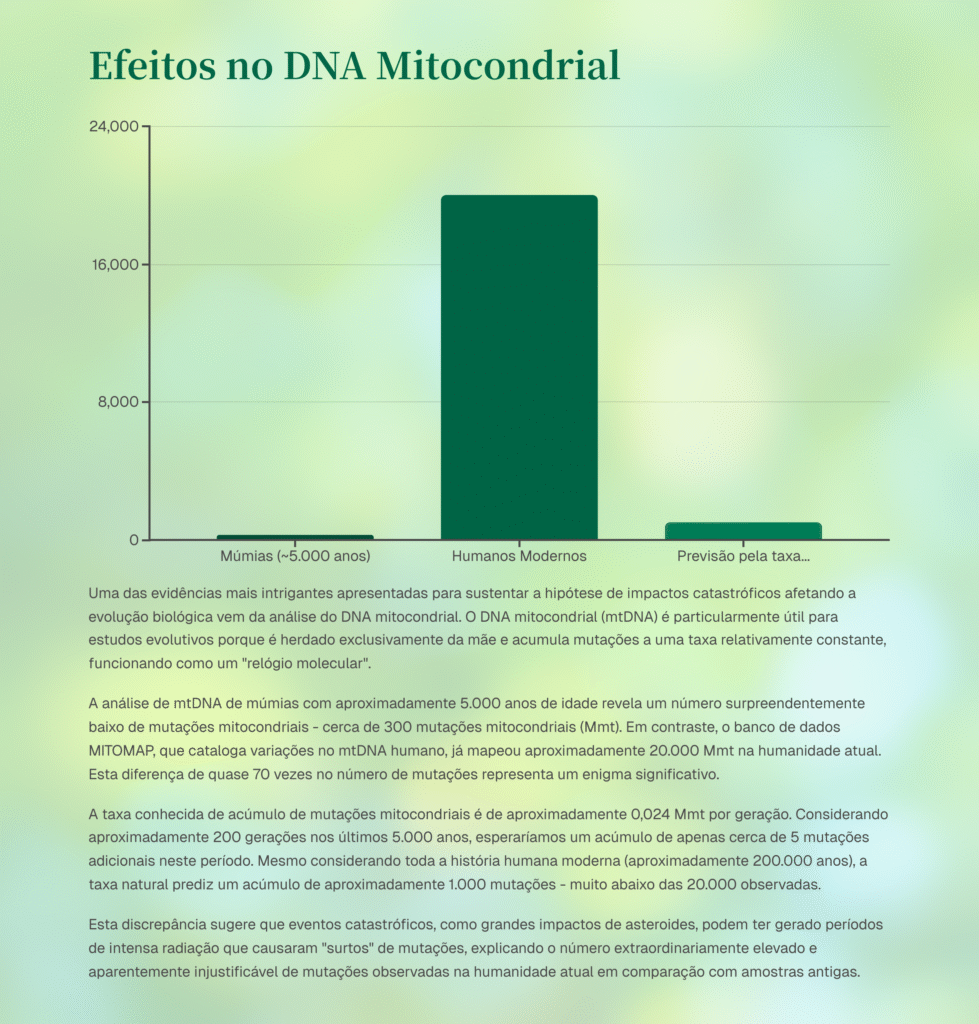

Mitochondrial mutations play a key role in degenerative subspeciation (which is called evolution), genetic diversity, and population adaptation. However, the disparity between mutation rates observed in modern studies and estimates derived from ancient samples raises significant questions. Modern rates range from 1 to 2 mutations per million base pairs per generation, while rates estimated from ancient samples, which range from 200 to 300 cumulative mutations [ 210 ] when compared to current mutations (~19k) [ 211 ] yield a rate of ~24 mitochondrial mutations per generation. This discrepancy suggests that there was a mutation peak in this interval, thus justifying this exponential increase, which could occur if there were a catastrophic event full of ionizing radiation followed by a bottleneck effect under many abrupt environmental changes.

Mitochondrial Mutation Rates: Ancient and Modern Perspectives

Ancient Mitochondrial Mutations: The study of mutations in ancient DNA extracted from mummies and other prehistoric human remains provides valuable information about the evolutionary history of populations. Studies of Egyptian mummies and other prehistoric human remains suggest that the accumulated mitochondrial mutations in these populations may have numbered as many as 200–300 variants [ 212 ] . Analyses of Nubian mummies from Sudan dated to 2,000–3,000 years ago have identified approximately 150 unique mitochondrial mutations [ 213 ] .

Modern Mitochondrial Mutations: In contrast, modern genetic databases reveal a significant accumulation of deleterious mutations in humanity [7, 8]. The 1000 Genomes Project identified a broad spectrum of genetic variation, including over 88 million variants, consisting of 84.7 million single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), 3.6 million short insertions/deletions (indels), and 60,000 structural variants. The total number of mitochondrial DNA single nucleotide variants (SNVs) accumulated in modern humans is 19,811, as reported by MITOMAP.

Catastrophic Events as Inducers of Mutation Peaks

Ionizing radiation is a known mutagen that can cause DNA damage, resulting in increased mutation rates [4] [ 214 ] . Events such as nuclear explosions, volcanic eruptions, and asteroid impacts can expose organisms to elevated levels of radiation, leading to an accelerated accumulation of mutations [5] [ 215 ] . In addition to radiation, other environmental stressors, such as severe hypoxia, can compromise DNA repair systems [Lee et al., 2021] [ 216 ] .

Based on the most relevant studies on haplogroups L1, L2 and L3 , we were able to identify specific differences in mitochondrial SNP mutations , with a special focus on oxidative stress mutations . Here is a detailed comparative analysis [ 217 ] [ 218 ] [ 219 ] :

| Feature | Haplogrupo L1 | Haplogroup L2 | Haplogroup L3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Estimated origin | ~150 thousand years | ~90 thousand years | ~70 thousand years |

| Defining mutations | A→G in 769, 3594 | G→A in 10873, A→G in 7146 | T→C at 10400, G→A at 10398 |

| SNPs associated with oxidation | ND1: A3594G (OXPHOS change) | COX1: A7146G, ND5: T12705C | ND3: T10400C, CYTB: G14766A |

| Density of conserved SNPs | High (rRNA and tRNA) | Moderate (ND4, COX2) | High in functional genes (ND5, ND3) |

| Presence of oxidative mutations | Yes, associated with NADH and Complex I pathways | Yes, especially in Complex IV. | Sim, incluindo mutações térmicas adaptativas |

| Seleção natural predominante | Purificadora | Mista (neutra e positiva) | Mais positiva (expansão fora da África) |

Evidências de Picos de Mutação em Populações Antigas

Estudos de DNA antigo revelaram padrões de mutação que coincidem com períodos de estresse ambiental, sugerindo que eventos catastróficos influenciam a diversidade genética[220]. A análise de populações que sobreviveram a desastres naturais mostra um aumento nas taxas de mutação em comparação com populações que não foram expostas a tais eventos[221].

| Haplogrupo | Origem estimada | Significado Evolutivo |

|---|---|---|

| L1 | África Central (~150 kya) | Um dos haplogrupos mais antigos. Associado à primeira dispersão humana. |

| L2 | África Ocidental (~90 kya) | Derivado de L1. Frequente em populações da África subsaariana. |

| L3 | África Oriental (~70 kya) | Dele se originaram os haplogrupos M e N (linhagens fora da África). |

Mutações Oxidativas Destacadas nos Haplogrupos Mitocondriais

As mutações oxidativas no DNA mitocondrial representam marcadores importantes para compreender como os organismos respondem ao estresse oxidativo, seja ele de origem ambiental, metabólica ou resultante de exposição a radiação. Nos haplogrupos L1, L2 e L3, identificamos padrões específicos destas mutações que podem ter relevância para a compreensão da adaptação humana a diferentes condições ambientais, incluindo possíveis períodos de aumento de radiação associados a eventos astronômicos.

| Gene | SNP | Presente em | Efeito provável |

|---|---|---|---|

| ND1 | A3594G | L1 | Alteração da cadeia de transporte de elétrons (ETC) |

| COX1 | A7146G | L2 | Leve impacto na eficiência do Complexo IV |

| ND3 | T10400C | L3 | Substituição conservativa com impacto térmico |

| CYTB | G14766A | L3 | Associada à variação metabólica adaptativa |

| ND5 | T12705C | L2 e L3 | Alteração moderada na oxidação do NADH |

| Região Afetada | Tipo de SNP mais comum | L1 | L2 | L3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| D-loop | Transições C→T, G→A (oxidativas) | Frequentes, mutabilidade alta | Frequentes, algumas exclusivas | Frequentes, compartilhadas com M/N |

| ND5 | A→G, G→A | Mutações conservadas | SNPs associados a adaptação energética | Alta densidade, compatível com migração |

| CYTB | G→T (transversão oxidativa) | Baixa frequência | Média frequência | Alta frequência, sugerindo pressão seletiva |

| rRNA 12S/16S | Mutações neutras ou regulatórias | Algumas posições variantes | Mais polimorfismos | Menos mutações — alta conservação |

| COX1 | SNPs sinônimos e não sinônimos | Mutações dispersas | Algumas variantes comuns | SNPs funcionais relacionados a bioenergética |

Estas diferenças sugerem trajetórias evolutivas distintas, possivelmente influenciadas por diferentes exposições a radiação ou outras fontes de estresse oxidativo ao longo da história evolutiva humana. A correlação temporal entre o surgimento destes haplogrupos e períodos de possível aumento de atividade astronômica, como bombardeios de meteoritos, oferece uma perspectiva intrigante sobre possíveis fatores externos que podem ter influenciado a evolução do genoma mitocondrial humano.

Kenney et al. (2014)[222] observaram que haplogrupos africanos (L1/L2) mostravam maior resistência ao estresse oxidativo, com perfil de SNPs menos propenso a mutações patogênicas em comparação com linhagens europeias. Wallace (2013)[223] propôs que as mutações acumuladas ao longo da linhagem L1 → L3 incluíram SNPs funcionais favorecendo o desempenho bioenergético em ambientes menos tropicais, onde o estresse oxidativo e térmico mudou. Ma et al. (2014)[224] identificaram que L2 e L3 contêm SNPs associados a adaptação metabólica, sendo alguns compatíveis com pressões de radicais livres em ambientes novos.

Mecanismos de Mutagênese Induzida por Catástrofes

O dano direto ao DNA por radiação e toxinas, junto com o estresse celular, pode resultar em um reparo de DNA prejudicado[225]. O impacto na fidelidade da replicação do DNA mitocondrial pode contribuir para a acumulação de mutações[226]. A exposição a radiações ionizantes superiores a 2 Gray resulta em uma deterioração significativa na atividade da PARP1, uma enzima crucial na detecção de lesões de DNA [Smith et al., 2022][227]. A hipóxia severa, frequentemente associada a eventos catastróficos, compromete significativamente os sistemas de reparo do DNA em níveis moleculares [Lee et al., 2021][228]. A radiação ionizante induz degradação proteolítica de sensores críticos como PARP1 e componentes do complexo MRN, comprometendo os mecanismos de reparo [Kim et al., 2020][229].

Implicações Degenerativas

Picos de mutação podem atuar como um motor de rápida adaptação, onde mutações mitocondriais desempenham um papel chave na degradação humana[230].A flagrante discrepância nas taxas de mutação pode ser interpretada à luz da teoria de que eventos catastróficos induzem picos de mutações. A radiação, como um agente mutagênico, pode explicar o aumento observado nas mutações modernas em comparação com as antigas históricas. A seleção natural (sobrevivência natural empobrecedora e diminuidora do pool gênico, porque a natureza não tem capacidade de selecionar nada) pode atuar sobre essas mutações, favorecendo aquelas que conferem vantagens adaptativas em ambientes alterados [231]. No entanto, o acúmulo de mutações deletérias leva à degeneração genética e ao aumento da suscetibilidade a doenças.

Therefore, since NEA impacts inevitably happened, it is plausible that they—and mostly only they—caused the mass extinctions in Earth history (as hypothesized by Raup), even if evidence for specific extinctions is lacking. What other process could possibly be as effective? And even if one or more extinctions had other causes, the largest asteroid/comet impacts during the Phanerozoic cannot avoid having left traces in the fossil record. [ 232 ]

New models for the formation of the Earth’s mantle have been proposed mainly by teams of creationist geophysicists linked to John Baumgardner [ 233 ] who also questioned absolute methods, through tests that contrast ages attributed by the unexpected omnipresence of carbon 14 (due to its short half-life) in materials of organic origin embedded in rocks considered to be around millions and billions of years old [ 234 ] [ 235 ]

The entire earth is full of signs of gigantic catastrophes with innumerable textural and sedimentological signs [ 236 ] revealing that they occurred recently, the salt seas, the pre-salt layers containing oil from the burial of forests of seaweed mixed with living beings, the gigantic igneous rocks scattered around the world such as the innumerable rocks of Petrópolis, Sugarloaf Mountain and Corcovado (Rio de Janeiro in Brazil, which is an uplifted platform, a kind of bubble of the marine platform) and quadrillions of large and small boulders scattered around the earth. The craters of multiple asteroids, the immense width and extension of sedimentary layers up to the Pleistocene, contrasted with the width of current deltas (which will continue to form under the same width pattern), the igneous formations with little sedimentation or weathering above them, attest that a gigantic and terrible accident has just happened here. Some isochronal perspectives also match the recent asteroid shower hypothesis such as:

1) Carbon 14 in datable quantities, present in Phanerozoic rocks considered to be 300-500 million years old, and also in uncontaminated diamonds embedded in these rocks, were tested in the Los Alamos laboratory by geophysicist Dr. John Baumgardner and team, published in 2004, and revealed that such rocks are recent and cannot be hundreds of millions of years old or even more than 50-70 thousand years old. New models for the formation of the Earth’s mantle have been proposed mainly by teams of creationist geophysicists linked to John Baumgardner [ 237 ] who also questioned absolute methods, through tests that contrast ages attributed to the unexpected omnipresence of carbon 14 (due to its short half-life) in materials of organic origin, embedded in rocks considered to be around millions and billions of years old [ 238 ] [ 239 ]

2) Trillions of sharp stones on the ground reveal that they existed recently because their edges would be worn down if they were old. In the same terrain, we find one next to the other, one rounded and the other sharp. Now, was the erosion that rounded the edges of one of the same material on the same terrain not capable of rounding the other? Their repetition in the geological strata unites their recent age to each other, in addition to revealing a recent gigantic disaster that created them.

3) Rocks that have been slightly worn by the impact of strong waters in waterfalls in various terrains considered old, linking them to a recent and common time.

4) Repetition of fossil forms under the light of the observation of modificational evolution or the strong influence that the environment exerts, changing the forms (morphology) of living beings, tells us that this morphological reproduction in “stasis”, permanent, of the same forms, of repeated taxonomy, only confirms that they lived in the same period and in the same environment, whereas our observation of the plastic behavior of living beings condemns the idea that they belonged to different times for supposed millions of years. The reproduction of fossil forms of living beings (Simpson, 1944 [ 240 ] , Benton 2009 [ 241 ] ) also demonstrates the burial of almost all populations of species on Earth (because if there are environmental and time changes, we have never had permanence of the same physical forms). And even if one or more extinctions have other causes, the largest impacts of asteroids/comet before (larger) and during the Phanerozoic cannot avoid leaving traces or being responsible for the fossil record. [ 242 ]

5) A meia-vida curta do DNA (sobretudo sob picos de mutações/radiações), o intransponível tempo de espera para explicação inclusive o saltacionismo evolutivo de Gould[243][244][245][246][247][248][249][250][251][252][253], explicitado nas publicações de vários cientistas, entre eles, John C Sanford[254][255][256][257][258], junto com o geofísico John Baumgardner e outros, ao mesmo tempo que encurta a possibilidade de tempo dos seres vivos na terra[259][260], reúne todos os seres vivos a uma época recente.

6) A queda de grandes bólidos e seus efeitos elétricos criando plasmas tem o poder de destruir a confiança na “constância de decaimento” em sistema “fechado” e nos faz prever rochas “envelhecidas radiometricamente” pela tração dos ponteiros do relógio radiométrico como demonstrar inúmeras técnicas patenteadas de descontaminação usando tração de decaimento em sistemas de tração de partículas e funcionamento de tokamaks acelerando elétrons. A decisão de acontecimentos separados pelo tempo , como a queda do Chicchulub tendo causado o Dekkan (Richards, 2015[261] Chatterjee, 2008[262]) nos impedem de aceitar que tais acontecimentos unidos um ao outro, estejam separados por milhões de anos. Uma hipótese [263] do Dr. Kutz, baseado em impacto, propõe que a depressão amazônica é resultado de deformação tectônica na intersecção de ondas de choque sísmicas originadas de dois grandes impactos planetários: o impacto de Chicxulub na Península de Yucatán (~66 Ma) e um impacto hipotético anterior próximo à Fossa das Marianas. O trabalho explora a possibilidade de amplificação antipodal em larga escala de energia sísmica e efeitos de interferência como mecanismos de deformação em escala continental. Utilizando ferramentas de geoinformática (ArcGIS, GPlates), dados topográficos e gravimétricos (SRTM, GEBCO, GRACE), e análogos planetários comparativos (Marte, Mercúrio, Lua), o estudo delineia um modelo geodinâmico sintético explicando a origem da bacia Amazônica como uma geoestrutura pós-impacto; Hipotetiza-se que a interferência de ondas sísmicas e tensão tectônica criada após os impactos pode ter moldado uma espécie de centro côncavo entre os Andes e a Cordilheira Meso-Atlântica, que favorece tanto o acúmulo de água quanto o desenvolvimento de um clima úmido e um ecossistema único na Amazônia. Com efeito, a Amazônia não seria apenas uma bacia geológica, mas uma estrutura secundária – formada como resultado de eventos de impacto de alcance global. O primeiro evento-chave neste modelo é um alegado impacto na região da atual Fossa das Marianas, que pode ter ocorrido antes da ruptura de Gondwana. A hipotética queda de um grande corpo celeste com alta energia cinética nessa área poderia ter gerado uma enorme onda sísmica, deformando a crosta oceânica e continental no lado oposto do planeta. Essa ocorrência antípoda pode ter resultado na formação da elevada Cordilheira Meso-Atlântica, que é hoje a linha limítrofe de propagação de placas litosféricas. As hipóteses de impacto também assumem que a Cordilheira Meso-Atlântica – em vez de ser unicamente o resultado da deriva continental – pode ter sido parcialmente formada como resultado do soerguimento antipodal da crosta terrestre após o impacto na região da Fossa das Marianas. Isso confere à estrutura da cordilheira características muito mais dinâmicas e cataclísmicas do que se assumiu anteriormente, com implicações importantes para a geo-história do Atlântico e sistemas terrestres associados, incluindo a Amazônia. Imprtante deliniar o efeito dominará estes impactos, como tendo possível relação.

8) Tecidos moles de minúsculos “bifes” endurecidos de tiranossauro-rex preservados nos impedem de concluir que sua extinção foi a muito tempo, mas combina entre evidências de evidências (76) que ela foi recente e não a 68 milhões de anos como a geocronologia convencional afirma. fossilização) de tiranossauro -rex, datados em “absurdos” chamados de “absolutos” 68 milhões de anos, refutados aqui e ofertas de outros como Triceratops horridus onde se diz (Armitage, 2013)[264].

Enquanto a geocronologia se mativer “absoluta” a ciência se transforma mais em uma stand up de comédia tentando nos convencer da milagrosa preservação de moléculas orgânicas [265][266][267][268][269][270][271] que um ambiente consciente que dialoga com a realidade e idade real de orgânicos.

9)A humanidade teve pico de acúmulo de genes deletérios entre 5 a 10.000 anos atrás e mais precisamente entre 2 e 6.000 anos atrás

Este artigo da Nature relatou na tese de Crabtree sobre nosso intelecto frágil[272] e previsão de aumento exponencial de doenças neurológicas, nos mostra que houve início de acúmulo de genes deletados entre 5 a 10.000 anos atrás, numa verdadeira explosão deles[273], como revela este estudo publicado[274]:

“Estudos em larga escala de variação genética humana dizendo assinaturas de recente crescimento populacional explosivo, notáveis por um excesso de variantes genéticas raras, revelando que muitas mutações surgiram recentemente. Para avaliar quantitativamente mais a distribuição das idades de mutação, nós resequenciamos 15.336 genes em 6.515 indivíduos de ascendência americana e Africano Europeu e inferir a idade de 1.146.401 variantes autossômicas de nucleotídeo único (SNVS). Nós estimamos que cerca de 73% de todos os SNVs codificadores de proteínas e cerca de 86% de SNVs previstos para serem excluídos nos últimos anos 5.000-10.000. deletérios em genes essenciais e mendeliana doença em comparação com os afro-americanos, de acordo com briga seleção purificadora, devido à dispersão Out-of-Africa”.

Temos hoje o segundo banco de dados BLAST entre 15 a 88 milhões de mutações com ” uma ampla espectro de variação genética, no total, mais de 88 milhões de variantes (84,7 milhões de polimorfismos de nucleotídeo único (SNPs), 3,6 milhões de inserções / exclusões curtas ( indels) e 60.000 variantes estruturais[275][276][277]em genes germinativos 100.000[278]. Se temos um acúmulo de 150 mutações deletérias a cada 25 anos (geração), fica fácil mensurar quando aproximadamente natureza pureza genética[279]. Um dado super interessante resumo do Dr. Marcos Eberlin[280], unindo as taxas mutacionais e picos percebidos, que se acumulam geração após geração, e em seguida dividindo por geração em relação ao total de mutações identificadas no genoma humano[281] . Descobrimos que a apenas 6 a 12.000 anos, ou em torno de 10.000 anos[282] nós temos pureza genética[283][284][285][286][287][288][289] e que vivos e mortos não poderiam estar tão afastados; ou seja, isso confirma o relato bíblico arqueológico de Gênesis quando fala dos ancestrais iniciais Adão e Eva[290][291], bem como confirma genealogias estatísticas em torno de 6.000 anos como distância temporal dos patriarcas ancestrais da humanidade [292][293][294][295][296][297][298][299][300] sendo que, desde 2004, já se admitia que dos atuais vivos, “o MRCA (ancestral comum mais recente) de todos os humanos atuais viveu apenas alguns milhares de anos atrás.[301]

11) O Contraste fóssil revela catástrofe que modificou o ambiente

A mudança drástica no ser vivo indica mudança drástica de ambiente[302][303][304]. Não temos gigantes sendo produzidos pela evolução hoje, hoje baleias e girafas estão em extinção, mas no registro fóssil eles são abundantes[305][306][307][308][309] . A mudança de ambiente pressionou os seres vivos a se adaptarem, variando, e consequentemente empobrecerem geneticamente, uma dessas mudanças pode estar ligada à atmosfera do planeta Terra, que tem maior concentração de oxigênio o que favorece ainda mais as formas de vida, longevidade, tamanho, e controle de patógenos como vírus, bactérias e fungos. ventiladores, balão de oxigênio e ozonioterapias[310]. O prefeito de Itajaí-SC, Brasil, médico, Dr. Volnei Morastoni, tem recomendado a aplicação retal de ozônio para pacientes que apresentam sintomas do novo coronavírus SARS-CoV-2 que manifesta Covid-19. Alguns ensaios clínicos foram publicados confirmando a eficiência desta técnica centenária para Covid-19[311] [312]. A técnica já conta com mais de 3.500 artigos no Pubmed e mais de 8.000 artigos no Science Direct e desde a patente de Tesla em 1896 que se sabe dos benefícios múltiplos da ozonioterapia atualmente no combate a 264 doenças incluindo efeitos antivirais, oxigenação, aspectos antiinflamatórios e antidiabéticos[313][314][315], melhorando a circulação, combatendo a hipertensão[316], grávidas hipertensas[317], doenças de pele[318] o que coloca a técnica como converte de benefícios conjuntos a pacientes de risco, tantos, que ameaçam centenas de patentes de medicamentos, provocando perseguições de agências do governo, e da mídia, muitas vezes controladas por lobbys da indústria farmacêutica. Neste contexto dos benefícios do oxigênio, percebemos que a terra era ainda mais adaptável a vida, ainda mais bem projetada, e na sua falta, temos o aumento da entropia genética nas suas formas EGI e EGP (Entropia Genética Individual no envelhecimento que vai acumulando mutações , e EGP, populacional, onde as populações vão acumulando mutações e empobrecendo seu pool gênico).

Sem Datações e Períodos Temos Simplesmente Estratos